Tuffuor v Attorney-General: The Man Behind the Controversy (1)

The approval processes for Supreme Court Justices and Chief Justices generally go according to plan. But not quite so in the case of Justice F.K. Apaloo.Justice Apaloo was in a lot of ways a man in his own class. And this meant that he was confronted by unique set of challenges. He was educated at A.M.E. Zion School and Accra Academy. He later went to University College, Hull to read law. He was called to the English Bar by the Middle Temple in 1950. He then returned to Ghana to practice law. He practiced in Accra until 1958 when he left to set up a practice in Ho (when the High Court in Ho was opened).

In 1960, he was elevated to the bench as a High Court judge. Six years later, he was appointed to the Court of Appeal and by 1971, he was a Supreme Court Judge. Six years later, he was appointed as Chief Justice. But it would not take long for his position as Chief Justice to be threatened.

1979 it was. There was a new constitution. There was a new government. The new constitution had changed the court structure. Prior to the 1979 constitution, the superior courts of judicature comprised the High Court and the Court of Appeal. The 1979 constitution introduced a Supreme Court as the highest court of the land. The 1979 constitution gave the president (then Hilla Limann) the power to appoint Supreme Court Justices and Chief Justices in consultation with parliament and the judicial council respectively. The constitution provided that anyone who held office as a justice of the superior court of judicature will be deemed to have been appointed as a justice of the Supreme Court as at the date that the constitution came into force.

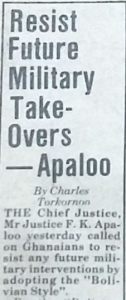

In stark variance with the clear words of the constitution on the appointment of justices of the supreme court, Parliament invited Mr. Apaloo to be vetted for approval first as a member of the Supreme Court and secondly as Chief Justice. Justice Apaloo appeared before Parliament’s appointments committee on 7 August 1980. At the Parliament, Justice Apaloo called on Ghanaians to resist future military intervention by adopting the “Bolivian Style”. According to him “everybody must say no to coup makers; judges and magistrates must not sit in court, no schools, no social and commercial activities and the coup makes will be subdued.”

In stark variance with the clear words of the constitution on the appointment of justices of the supreme court, Parliament invited Mr. Apaloo to be vetted for approval first as a member of the Supreme Court and secondly as Chief Justice. Justice Apaloo appeared before Parliament’s appointments committee on 7 August 1980. At the Parliament, Justice Apaloo called on Ghanaians to resist future military intervention by adopting the “Bolivian Style”. According to him “everybody must say no to coup makers; judges and magistrates must not sit in court, no schools, no social and commercial activities and the coup makes will be subdued.”

But his presence before the Appointments Committee of Parliament was always going to be controversial. A member of the Committee, Mr.Thomas Broni of the Popular Front Party (PFP) raised an objection to the constitutional basis for the vetting of Mr. Justice Apaloo. He argued that since a Chief Justice had to be in place before the swearing of the President, a Vice President and the Speaker of Parliament, the vetting of Mr. Justice Apaloo could give rise to a situation where somebody could challenge that Ghana had no President, Vice-President and Speaker. With this, Mr. Broni disassociated himself from the work of the committee and walked out. The committee continued regardless.

Take note. Justice Apaloo did not take advantage of the objections raised by Mr. Broni to question the validity of the proceedings in Parliament. Regarding the validity or otherwise of his presence before the Appointments Committee of Parliamentary, Justice Apaloo noted: “I think it is morally good to be vetted since all my colleagues have been vetted and secondly it is a purely constitutional issue.” What Justice Apaloo meant by his presence being a merely constitutional issue is hard to fathom but he will soon change his tone – slightly.

Justice Apaloo was quizzed regarding his assets. The committee found that he owned three houses in Accra, Ho and Woe, near Keta. Justice Apaloo explained that with the exception of his house in Accra, all the other houses he had were acquired during his private legal practice. He was also probed about allegations that two of his daughters had travelled to London at the expense of the state. Justice Apaloo again explained that he paid the air ticket of one of his daughters from his own account. He explained also that his other daughter used a concession granted to staff of Ghana Airways because his uncle was one of the senior managers of Ghana Airways.

But the most controversial of the allegation levelled against him had to do with his tax obligations. It was alleged that Justice Apaloo was owing more than 16,000 cedis in tax obligations which had not been paid. Justice Apaloo explained once again that he had paid all the amount and had been credited with some amount due to an error in the computation of his tax liabilities.

Not everyone was pleased with Justice Apaloo’s explanation of how he handled his tax obligations. On 14 August 1980, there was a bold headline in the People’s Daily Graphic: “C.J MUST GO”. The headline was attributed to a statement made by Mr. Kwame Nyanteh, an industrialist and a failed presidential aspirant. According to Mr. Nyanteh, although the Chief Justice had paid all the taxes that he owed, his behaviour was untoward. He further noted that Justice Apaloo’s integrity must be taken with a pinch of salt. He also wondered why Justice Apaloo was allowed to reschedule his tax arrears while revolutionary punishments were meted out to other defaulters.

Not everyone was pleased with Justice Apaloo’s explanation of how he handled his tax obligations. On 14 August 1980, there was a bold headline in the People’s Daily Graphic: “C.J MUST GO”. The headline was attributed to a statement made by Mr. Kwame Nyanteh, an industrialist and a failed presidential aspirant. According to Mr. Nyanteh, although the Chief Justice had paid all the taxes that he owed, his behaviour was untoward. He further noted that Justice Apaloo’s integrity must be taken with a pinch of salt. He also wondered why Justice Apaloo was allowed to reschedule his tax arrears while revolutionary punishments were meted out to other defaulters.

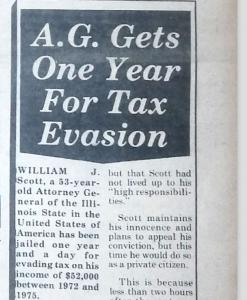

There was a very curious story of an Illinois Attorney-General who had been sentenced to serve time for tax evasion – as if to say that the same approach should be followed in the case of Mr. Justice Apaloo.

There was a very curious story of an Illinois Attorney-General who had been sentenced to serve time for tax evasion – as if to say that the same approach should be followed in the case of Mr. Justice Apaloo.

Long story short – on 16 August 1980 Parliament’s Appointments Committee came to the conclusion that Justice Apaloo was not fit to be Chief Justice.

At this stage, the rejection of Justice Apaloo as Chief Justice was generating a lot of buzz and public discussions – with some people reading ethnocentric meanings into it.

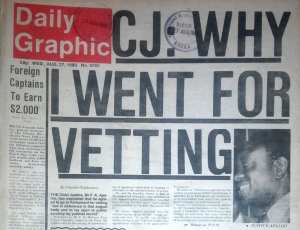

On 27 August 1980, Mr. Justice Apaloo sought to explain why he appeared before Parliament’s Appointment Committee when there was no constitutional basis for that. Remember he had said earlier that the reason he appeared before Parliament was because he thought he had a moral duty to do so. Well, now his reasons are slightly different. For him, he appeared before the Appointments Committee of Parliament out of deference to that august body and also to lay open to public scrutiny his judicial record. Mr. Justice Apaloo recounted that the official reason given for his invitation to Parliament was that: “to qualify as Chief Justice sitting in the Supreme Court, your appointment will have to be approved by Parliament.” “I did not accept that as the correct requirement of the constitution. I agreed to go to Parliament out of deference to that August body and to lay open to public scrutiny my judicial record”, he said.

On 27 August 1980, Mr. Justice Apaloo sought to explain why he appeared before Parliament’s Appointment Committee when there was no constitutional basis for that. Remember he had said earlier that the reason he appeared before Parliament was because he thought he had a moral duty to do so. Well, now his reasons are slightly different. For him, he appeared before the Appointments Committee of Parliament out of deference to that august body and also to lay open to public scrutiny his judicial record. Mr. Justice Apaloo recounted that the official reason given for his invitation to Parliament was that: “to qualify as Chief Justice sitting in the Supreme Court, your appointment will have to be approved by Parliament.” “I did not accept that as the correct requirement of the constitution. I agreed to go to Parliament out of deference to that August body and to lay open to public scrutiny my judicial record”, he said.

He denied allegations that he had presided over the case of a former client at the High Court. He denied all allegations of bias and judicial impropriety. In his conclusion, he defended his track record and integrity on the bench as a judge. He stressed “…I was promoted to the supreme court established under the second republic in 1971 and further promoted chief justice in 1977. No one thought I had done anything remotely resembling judicial impropriety.” He stressed that no complaint had been made to any public authority because in both 1977 and 1979, he was awarded National Honours for distinguishing public service and administration of justice in the country.

While the back and forth was ongoing in the media and in the public arena, someone decided to take the bull by the horn and have this matter resolved conclusively. In comes Mr Tuffuor.

Samuel Alesu-Dordzi is an Editor of the Ghana Law Hub.

Good read. Thanks.

However, please enlighten me. How could Justice Apaloo have become a Justice of the SC in 1971, when same was only a creation of the 1979 Constitution?

Send me news directly