By: Claudia N.A. Coleman (Private Legal Practitioner)

Physical spousal abuse became a regular theme in Media reports in the late 1990s, thus resulting in the establishment of the Women and Juvenile Unit (WAJU) of the Ghana Police in 1998; a specialised unit that handled crimes against women and children. These actions resulted in the Government of Ghana enacting a few national laws to protect women’s rights and outlaw violence against women and girls. These included a provision in the 1998 Criminal Code Amendment Act, as well as legal amendments criminalising certain harmful traditional practices, such as widowhood rites, female genital mutilation (FGM) and child abuse.

Following several years of advocacy efforts by key civil society and women’s rights organisations, the Media and International Bodies, the Government and Parliament of Ghana enacted the Domestic Violence Act (Act 732) in February 2007. This was followed by the formulation of the National Policy and Plan of Action (NPPOA) developed by the former Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs in 2008. The policy laid out the specific roles of key stakeholders that would effectively implement the Domestic Violence Act.

The Act outlines a comprehensive legal framework for the prevention of and protection against domestic violence and criminalises various acts of physical and sexual violence, economic and psychological abuse and intimidation in domestic relations.

Ghana’s domestic violence legislation takes a broader and, arguably, culturally sensitive approach to access to justice, when compared with other countries such as Chad and Eritrea.

Although much effort was put in place for the protection of women, the framers of the law recognised that men also suffered domestic violence therefore WAJU was replaced with the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit [DOVVSU] after the Act was enacted to include all sexes.

Second, the definition of domestic violence includes various forms of economic abuse, in addition to more conventional definitions of sexual and physical violence.

Third, the Act allows for mediation by alternative dispute resolution methods.

The Act also acknowledges that perpetrators and victims do not have to be married or related by blood ties and applies to domestic workers as well.

The Act also criminalises elements of domestic violence.

Notwithstanding this innovative legislative work, much remains to be done.

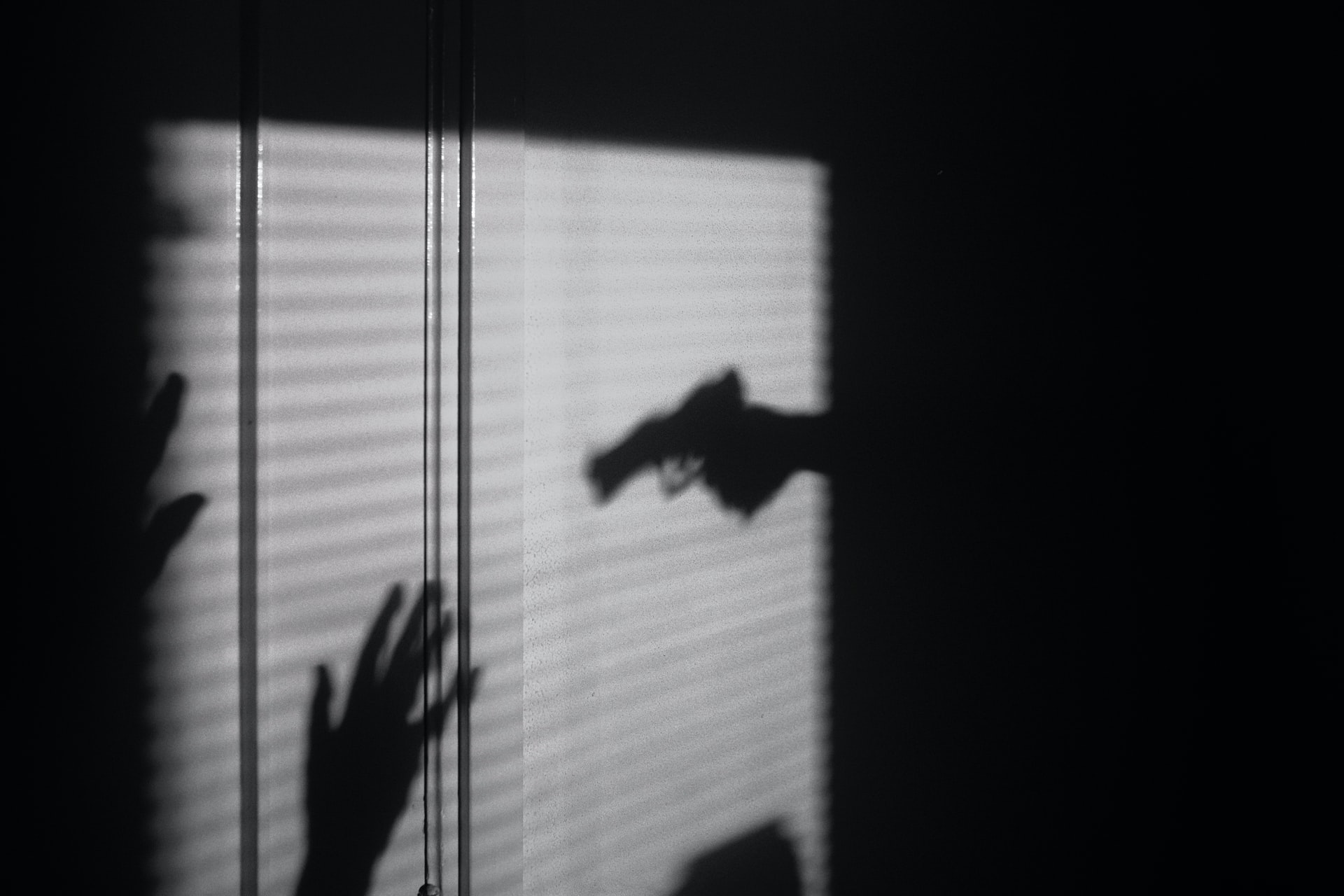

This article has come about due to the recent happenings of domestic violence in the country. In March 2021 alone, the media reported five killings of women by their partners. Discussions surrounding this issue sought to draw the attention of law makers to take another look at the Act especially the welfare of the children in such relationships.

It also seeks to highlight some gaps of the Act and further recommend for its amendment.

Gaps identified with legislations in relation to domestic violence.

1.Elements of domestic violence

Section 1 of the Act indicates that Domestic violence means engaging in the following within the context of a previous or existing domestic relationship: an act under the Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29) which constitutes physical abuse, sexual abuse, economic abuse, and emotional, verbal or psychological abuse and … is likely to detract from another person’s dignity and worth as a human being.

Though these elements of domestic violence are relevant there are others that should also be considered due to its frequent occurrence in domestic relationship; namely: discriminatory abuse (unequal treatment, denying basic rights to healthcare, education particularly in domestic settings where the victim is not the biological child of the respondent), neglect and acts of omission (especially parents neglecting the welfare of children), exploitation of a member(s) in a domestic relationship, abandonment (especially a spouse deserting the home) and social abuse (acts of controlling behaviours).

2.Meaning of domestic relationship

Another gap identified in the Act is the definition of what domestic relationship means under section 2. There is little consideration of the welfare of children per the meaning of domestic relationship. Although the long title of the Act depicts it as an Act to provide protection from domestic violence particularly for women and children, section 2 demonstrates there is not much under the Act for children. It appears what constitutes domestic violence was more focused on adults than on children. In a study conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service and the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection revealed that exposure to violence in childhood was found to be strongly related to the likelihood of an individual being a victim of violence in adulthood. The direct exposure of children to violence within such household may result in children being more likely to experience (either being a perpetrator or victim) domestic violence later in life and thus becoming a cycle.

With guidance from the Children’s Act 1998 (Act 560), this provision should be amended for a proper consideration of children in domestic relationship who may be the primary or secondary victims of domestic violence thus curbing this cycle.

3.Assistance from the Police

Again, another gap under the Act is Section 7 that asserts that a police officer shall respond to a request by a person for assistance from domestic violence and shall offer the protection that the circumstances of the case or the person who made the report require, even when the person reporting is not the victim of the domestic violence. The question that comes to mind is can the police provide shelter to a victim because most victims report physical abuse and will like to seek refuge from the abuser(s). It is recommended that this Section be rephrased to include exact assistance the police can provide victims because the police are not in the position to offer protection in all circumstances.

4.Free medical treatment

Section 8 of the Act specifies that a victim of domestic violence who is assisted by the police to obtain medical treatment is entitled to free medical treatment from the State. However, studies have shown that in many hospitals, victims of physical violence who require emergency medical treatment, are required to make payment before receiving medical attention contrary to the provision of the Act.

It is interesting to note that medical centres were not included under the objectives of the funds per the Act. However, the law states that medical treatment will be free so the next question is how government expects these medical facilities offer free treatment to victims when they are not financially assisted.

It is recommended that law should be enforced to encourage victims report and seek early treatment.

5.Application of funds

One major challenge in Ghana is mainly the implementation of the laws and not necessarily the lack of it. The Act provides the establishment of support fund to victims of domestic violence and how this fund will be applied. However, the management of this fund is not given the needed priority since allocation of fund from government is so inconsequential. It is recommended that this provision of the law should be seriously addressed. Funds should be allocated to the relevant Agencies including medical facilities and NGOs that provide shelters to victims such as Ark Foundation and Pearl Haven.

6.Statutory separation

Another legislation that should be considered in the fight against domestic violence is the Matrimonial Causes Act 1971 (Act 367). It is recommended that the law should be amended to include a statutory separation provision, like other jurisdictions such as Australia and Ireland. This will enable victims of domestic violence apply to the courts for separation even as efforts are being made for reconciliation of the marriage. This will encourage victims of domestic violence in marriages that are less than two years seek refuge from their abusive spouses since the Matrimonial Act does not encourage the petition of divorce that are less than two years. Issuance of protection orders under this Act alone is not enough.

7.Other recommendations:

This article recommends that Religious bodies should supplement Government’s efforts. The options of temporary shelter from family, friends and religious bodies must be explored.

There should be sensitisation and education to these religious bodies to encourage their members report domestic violence instead of propagating permanence of marriage and advising victims endure the abuse thereby treating the violence as a family affair.

Victims should be given all the needed support from family, friends and religious leaders as they go back to normalcy instead of blaming them for the abuse.

Often, if victims perceive that they will be put in more danger by reporting, they will either be reluctant to report or refuse to do so, consequently, State Agencies like DOVVSU can in assessing the legality of the situation make the respondent sign a bond to be of good behaviour even before the matter proceeds to court.

8.Conclusion

This article acknowledges the effort put in the fight against violence in general especially in the domestic settings to reflect chapter 5 of the 1992 Constitution. However, much more can be done when the relevant legislations are amended to deal with these identified gaps.

Leave a Reply