Dismantling the Retirement Age Architecture

The Supreme Court recently decided by a 5-2 majority that the 66-year-old Martin Amidu was eligible to be nominated, vetted and appointed to the office of the Special Prosecutor even though the mandatory retiring age from the public service is 60. It is good that this matter, albeit delayed, has ended. In a constitutional democracy, the Court has the last word and it has spoken. While other views are just that, they must nevertheless be aired for accountability purposes. All good judges crave for and accept honest, constructive feedback on a regular basis because they are acutely aware that their skills will atrophy, absent such feedback.

I would have voted with the minority on grounds that Parliament has no authority to create a public service position that subverts the retirement age scheme stipulated by the Constitution.

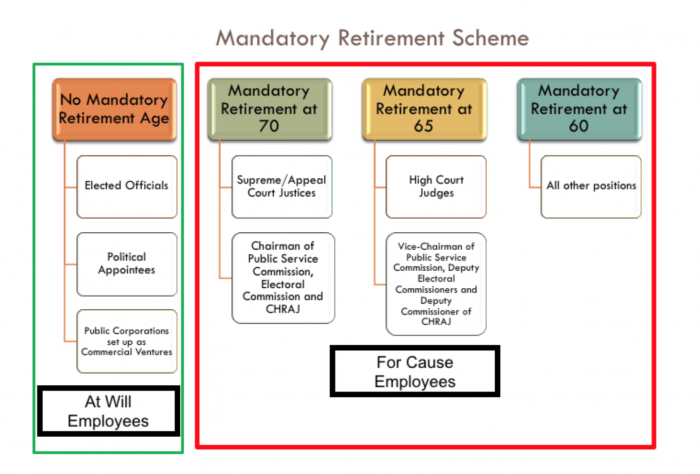

The Constitution creates two kinds of public officers, one who can be dismissed only for cause and the other at will. See the chart below.

At-will means that an employer can terminate an employee at any time for any reason, except an illegal one, or for no reason without incurring legal liability. Thus, at-will public officers are those who serve at the pleasure of their appointors. Elected officials normally serve for a fixed term. They hold a public office, as defined by Article 295, and are therefore properly classified as pubic officers. I categorize them as at-will officers only because the voters can dismiss them after the fixed term for any reason. Political appointees serve at the pleasure of their appointors, usually the President, who can fire them for a good, bad or no reason. At will public officers can also be employees of public corporations that are set up as commercial ventures. For instance, Act 740 establishes the Bui Power Authority with a mandate of developing hydroelectric power on sound commercial lines. The Bui Board appoints and determines the terms and conditions of the chief executive officer (CEO). The employment-at-will doctrine generally inhibits judicial second-guessing of discharge decisions, even if they are unfair, unfortunate or harsh. Because their tenure is hazardous at best, the Constitution specifies no mandatory retirement age for at-will employees.

A for-cause employment is one that can only be terminated without any further employer obligations under a set of conditions that are usually specified in the employment agreement. A for-cause employee would, therefore, have a legal remedy for the employer’s unjustified decision to terminate the employment relationship. For-cause public officers are normally career public officers whose employment survive the change in political leadership. Because their tenure is guaranteed while they act properly, the Constitution sets a mandatory retirement age. Here, the Constitution itself provides that a few in this category must retire at 70, others at 65 and all others at 60.

Article 295 provides that “the Public Service includes service in any civil office of Government, the emoluments attached to which are paid directly from the Consolidated Fund or directly out of moneys provided by Parliament and service with a public corporation. Article 190 provides that the Public Services shall include (a) the fourteen public services enumerated by the Constitution; (b) public corporations other than those set up as commercial ventures; (c) public services established by the Constitution; and (d) such other public services as Parliament may by law prescribe. The members of the Public Services fall in the “for cause” category, hence the command that they shall not be dismissed or removed from office or reduced in rank or otherwise punished without just cause. Similarly, they cannot be victimized or discriminated against for discharging their duties faithfully in accordance with the Constitution (see Article 191). The mandatory retirement age, and other constitutionally-determined terms of service, must be appreciated and understood within a historical context where the public service has been africanized, politicized and used to achieve partisan goals or to reward political loyalists to the detriment of overall public service efficacy.

The chart shows that unless otherwise included in the 65-years or 70-years bucket, a “for cause” public officer must retire at the age of 60. This is the essence of Article 199(1), which provides that “A public officer shall, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, retire from the public service on attaining the age of sixty years.” It is such a clear command that it is not capable of any other interpretation. This is why the Court, in the Appiah-Ofori case, rejected the argument that the Auditor General being appointed under Article 70 should retire at the age of 70. As the Court noted, on the question of mandatory retirement, the framers had made specific provisions for only some Article 70 office holders. Further, the Appiah-Ofori Court reasoned that the mere provision of a process of removal of the Auditor-General in accordance with that available to Justices of the Superior Court does not inextricably equate his office to Justices of the Court of Appeal (see Article 187(13)).

The Office of the Special Prosecutor was established by Parliament pursuant to its Article 190(1)(d) power. Thus, the Special Prosecutor is a for cause public service position. The person who holds the position is neither elected nor serve at the pleasure of the appointors. Even though it is incorporated, it is not set up as a commercial venture. Plainly, it is just a specialized prosecution position. Where Parliament establishes a public service, Article 190(3) provides that Parliament shall provide for its governing council, its functions and membership. Conspicuously missing from Article 190(3) is any hint that the retirement clause of Article 199 is subject, in anyway, to parliament’s establishment power.

In my opinion, just because the Constitution itself allows some for cause public officers to retire at 65 and 70, does not mean Parliament too can create positions that set the retirement age beyond 60 or otherwise effectively upset the constitutional retirement scheme. Otherwise, we are in a regime where all parliament needs to do is to create a Special Professor or Special Auditor-General position and stipulate that they serve for a 10-year term, which then allows them to be appointed after mandatory retirement for 10 more years.

The Constitution was Amended in 1996 to add Article 199(4), which provides that “Notwithstanding clause (1) of this article, a public officer who has retired from the public service after, attaining the age of sixty years may, where the exigencies of the service require be engaged for a limited period of not more than two years at a time but not exceeding five years in all upon such other terms and conditions as the appointing authority shall determine.” However, it has not been suggested that the Special Prosecutor has been appointed under this Limited Period contract. Nor has anyone identified the exigencies that will warrant the triggering of this clause. It has also not been suggested that the appointee retired from the public service after attaining the age of sixty years.

It is logically unpleasant for a Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to be retired mandatorily at 60 only to be appointed to another public service prosecutorial position for a fixed term. Whether one is in charge of prosecuting corruption or prosecuting armed robbers should not determine one’s retirement age. At least, that facially absurd regime is not in the Constitution. There is nothing special about the special prosecutor’s position that makes it invincible to the Constitution’s mandatory retirement scheme. He is a prosecutor who specializes in prosecuting corruption offenses.

Where the Constitution provides a clear, bright-line rule to govern the retirement of public service officials, Parliament cannot create public service positions that effectively have no retirement age. Nor should, in my opinion, the Supreme Court under the guise of a “purposive” approach sanction such a parliamentary adventure, thereby creating a for cause public official who is not subject to mandatory retirement. The Court’s holding puts the Special Prosecutor in a mezzanine section in the retirement framework illustrated by the chart at supra.

Likewise, while the Constitution sets a minimum age of 40 for the President and 21 for an MP, that does not mean Parliament too can start setting its own minimum age limits for other public service positions. In our polity, it is the Constitution, not Parliament, that is supreme. We must therefore be careful not to apply, even if unconsciously, doctrines that we inherited during our colonial history.

The Court’s reasoning that the office of the Special Prosecutor is critical, which therefore empowers Parliament to traverse Article 199(1), is at once flawed and at variance with the Court’s holding in the Appiah-Ofori case. In Appiah-Ofori, the Plaintiff canvassed similar arguments about the Auditor-General being an Article 70 appointee, whose functions are critical, and should therefore retire at seventy years in pari materia with Court of Appeal judges. Referring to the clear wording of Article 199(1), the Court rejected the argument. As the Constitution did not stipulate a specific mandatory retirement age for the Auditor-General, it followed that he or she must retire at sixty years. The legislative mandatory retirement age of sixty was upheld only because of its consistency with Article 199. Parliament could not have set the retirement age at fifty-five or seventy-five years.

While the Court concludes “emphatically by stating the category of public officers to which the Special Prosecutor has the closest affinity is the Article 70 office holders whose conditions, including the retirement age is pegged to that of the Justice of the Court of Appeal,” it is emphatically the case that being an Article 70 office holder is not dispositive of the holder’s retirement age as Appiah-Ofori emphatically demonstrates.

The Court also deduces that:

“the Special Prosecutor is a public officer whose office is analogous to that of the Commissioner for Human Rights and Administrative Justice, the Chairman of the Public Service Commission, Chairperson of the Electoral Commission, Chairman for the National Commission for Civic Education, Administrator of District Assemblies fund, etc., and not a public officer under Articles 190, 195 and 1999 of the Constitution.”

This deduction is based on nothing. The Special prosecutor’s office is more analogous to that of the Director of Public Prosecutions, except that the former is in charge of a narrower set of offences. However, it is not necessary to disagree with the deduction to see its irrelevance to the question of retirement age.

First, these are constitutional officers. The Special Prosecutor is not a constitutional officer. Second, what is unique about these constitutional officers is their mode of appointment (Article 70). They do not have the same terms and conditions of service and certainly do not have the same mandatory retirement age. Third, being an Article 70 appointee does not remove one from Article 190. For instance, the Auditor General, while appointed under Article 70, is a member of the Public Services under Article 190. His mandatory retirement age not being specifically provided for by the Constitution is determined in accordance with Article 199. Fourth, analogous or not, the Court seems to ignore a fundamental maxim that a legislation cannot undo a constitutional provision. If the Constitution sets a mandatory retirement age for the public service and excepts an office, the constitutional exception does not empower Parliament to create offices analogous to the excepted office with a mandatory retirement age that differs from the general one set by the Constitution. Taken together, the Court’s emphatic conclusion is emphatically problematic and without an emphatic foundation.

The Court’s COVID example, wherein an emergency can provide a constitutional basis for changes in the retirement age, undermines constitutional theory. A constitutional amendment, not a misguided application of purposive interpretation, is required if it becomes obvious that health workers, for instance, should be allowed to work beyond the mandatory retirement age. This COVID principle, if not rejected, will justify legislation to alter the presidential term limit.

It is both wrong and a distortion of the record for the Court to have relied on Parliament’s residual power under Article 298 or any other Article. Wrong, because Article 199 exhausts the retirement age issue. The residual power cannot be triggered where there is an express constitutional voice on a matter. A distortion, because Parliament itself declared that it was relying on its powers under Article 190(1)(d), which also resolves the issue of whether the office is part the Public Service. It is!

The Court’s holding that there was no clear prohibition, inference or language in the Constitution that barred Parliament from crossing the 60 years retirement age when fixing the tenure of office for certain critical office holders is fanciful. Article 199(1) is a very clear prohibition. Other than the exceptions provided by the Constitution itself, no law and no Court is permitted to set a retirement age for public officers in the public service. Article 199(1) does not distinguish among professional, technical, bureaucratic, or administrative personnel in the public service as the Court declares. Nor does it distinguish between critical and non-critical officeholders. It gives an unequivocal command — A public officer shall retire from the public service on attaining the age of sixty years.

Equally, there is no merit in the claim that public service officials who hold appointments for fixed periods are not subject to the mandatory retirement scheme. To be sure, appointments to the senior hierarchy of the public service can be made through contracts, open tenure or even limited engagements. However, contractual status notwithstanding, appointees remain public officers who are entitled to a nontaxable pension at the end of their service (Article 199(3)) and, therefore, are subject to the mandatory retirement scheme (Article 199(1)(4)). Otherwise, Article 199 is brutum fulmen. While the Court relies on Yevuyibor and Donkor, neither stands for the proposition that the Public Service can undermine Article 199 by merely offering contracts or limited term engagements. Au contraire, Yevuyibor affirms that the mandatory retirement age is binding on officials of the Public Service and Donkor says nothing about retirement age.

Article 199(1) and (4) provide a definite retirement age. They are not subject to any construction, narrow or broad, any more than the minimum voting age of 18 years is subject to construction. Bright-line rules, such as an age requirement, do not lend themselves to much debate about their interpretation and certainly do not require construction. Courts resort to construction when the constitutional text is so broad or so undetermined as to be incapable of faithful reduction to legal rules. Here, however, the Articles in question provide an objective retirement rule for public officials in the public service. The framers’ purpose of providing such an objective rule is to allow age-related questions about mandatory retirement in the public service to be answered in a straightforward and predictable manner.

Therefore, the Court’s claim that a narrow construction will do damage to the constitutional document is entirely far-fetched. Rather, what does damage to the Constitution and retards its growth as a living organism is the uncalled-for construction of its very categorical, unambiguous, and precise commands, such as the mandatory retirement age or by extension any age or term requirements therein. The Court’s “purposive” construction obstructs, rather than furthers, the framers’ purpose of imposing a mandatory retirement age for all public servants.

The Court’s extensive treatise on purposive interpretation and resort to Tuffuor added little value to its analysis and it failed woefully to apply the principles thereof. The treatise did not shed any light on the framers’ purpose of constitutionalizing the retirement age rather than leaving it to be determined as a statutory matter. It is becoming a worrying trend that whenever the Court decides to ignore the commands of the Constitution, it does so by offering an inconsequential treatise on these interpretive aids and offering a paean to the purposive approach.

Neither a purposive approach nor Tuffuor stands for the proposition that the clear words of the Constitution must be ignored. Nor do they stand for distorting or ignoring the record on what Parliament itself has relied on in enacting a law. In this case, both the 1979 and 1992 “Committees of Experts” were ad idem on constitutionalizing the retirement age for public officers to take it from the realm of politics. They were firm about the mandatory retirement age. Constitutionalizing the mandatory retirement age was part of a repertoire of procedures that the framers emplaced to guarantee the independence and integrity of the Public Services, thereby removing it from the direct or indirect control of the executive or other elected officials. Further, the 1996 amendment affirmed the mandatory retirement age and made a limited exception for extending it for fixed terms but only to cover exigencies. It is this amendment that must be construed narrowly so as not to swallow the main rule. A purposive analysis then should have rendered the impugned appointment unconstitutional since the appointee was not only above the retirement age in Article 199(1) but also above the maximum allowable extended limited engagement tenure in Article 199(4).

The Court’s extended discussion of why there is not a single retirement age for all public officers was entirely gratuitous because it was never an issue. Both parties acknowledged this fact, which is also apparent from a cursory reading of the Constitution. Moreover, the Court failed to offer a framework, similar to the one here, that ties together these seemingly disparate ages and could have provided a conceptual basis for classifying the Special Prosecutor position for retirement purposes or for settling future retirement age disputes.

The Court seems to take the unusual view that Parliament can traverse the mandatory retirement age since the Constitution itself creates some offices that have no mandatory retiring age. This seems to underappreciate the theory of constitutional supremacy. As Justice Dordzie notes, “one cannot call in aid provisions of the Constitution to support an Act when the Act in question is proved to be inconsistent with particular provisions of the Constitution.” Nor, I might add, can the Court list clauses from various Acts to launder the constitutional tort of an impugned Act. Either these Acts do not offend the Constitution or, where they do, they must fall with the impugned Act. There is no constitutional doctrine that constitutionalizes an unconstitutional Act merely because some other Acts too seem to have offended the Constitution. Thus, the catalogue of Acts, provided by the Court, to show how Parliament had addressed the terms and conditions of some other offices is not value-relevant. For instance, it is not unconstitutional for Parliament to set up a commercial venture public corporation whose “at will” employees’ retirement age is untethered from Article 199. On the other hand, sections of Acts that have offended the Constitution must be stricken down. I do not accept the Court’s position that striking down such unconstitutional sections will result in “chaos, anarchy and confusion in our society.” Rather, purposively construing the Constitution to remove the limits it imposes on legislative power or otherwise misconstruing even its bright-line rules is what will ultimately result in societal chaos, anarchy and confusion.

The framers have painstakingly and meticulously provided a retirement age architecture that the Court has undone in a rather cavalier way by ignoring its own precedents and distorting the parliamentary record on the Office of Special Prosecutor legislation. Article 199(1) is entirely meaningless if any transient parliament can create public service positions for which it does not apply. Except as provided in this Constitution means just that!!

Thus, it was entirely per incuriam for the Court to hold that Parliament has the flexibility and authority in appropriate cases to prescribe a retirement age different from the article 199 age as the exigencies of the job will require. No reading of Article 199 and all the committee of experts’ report will support such a construction. An Act that is contrary to the Constitution is no law at all. To declare otherwise, as the Court suggests with its stance on flexibility, is to undo the limits that the Constitution imposes on legislative power.

I do, of course, have concerns with the lack of uniformity in the mandatory retirement age of public servants and have indicated the need to amend the Constitution to make it uniform. For instance, the mandatory retirement age can be set at seventy years for all public service positions while still allowing voluntary retirement to commence at sixty years. Improvement in life-expectancy and the pressures on the pension fund are further reasons for such a change. But that is a far cry from suggesting that Parliament has the authority in appropriate cases to prescribe its own retirement age as the exigencies of the job will require. Exactly what would an appropriate case and an exigency be? Will Parliament similarly have the authority to prescribe its own minimum voting age in an appropriate case as the exigency requires?

Constitutional cases are seldom about the parties, who are at best nominal litigants. Thus, debates about such cases are not about the parties. Rather, such debates are about constitutional principles that have stare decisis value and become part of the body of law that are discussed in the law faculties. Robust debates about these cases are therefore necessary to situate them in the corpus juris.

A final noteworthy point is that the Supreme Court took more than 2 years to determine this case. This is not good enough. A question about the qualifications of a person to hold a certain office must be resolved immediately. Ideally, it must be resolved before the person ascends to that office. A delay in answering such a question is not just unjust, it also puts the Court in a precarious position where saying the appointee is disqualified raises questions about the Court’s wisdom in allowing an unqualified person to hold the position for 2+ years in violation of the Constitution. Unconsciously, such delays may then bias the Court toward a finding of constitutionality to avoid the dissonance of declaring unconstitutionality after allowing the unconstitutionality to persist for 2+ years.

Alas, this is not the first time that such an unacceptable delay has occurred. In fact, such delays, in time-sensitive constitutional cases, have become the norm. The Court should figure out a way to address this problem as it is causing the public to lose confidence in and respect for these delayed opinions. Many of these constitutional cases are about legal arguments and do not involve testimony from witnesses. They can be resolved much quicker than the current practices allow. The Court must do more to enhance judicial efficiency.

To conclude, Article 199(1) provides that “A public officer shall, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, retire from the public service on attaining the age of sixty years.” This is a simple bright-line rule that does not admit of fanciful interpretations or construction. Nor should its reach be curtailed by the establishment of fanciful public service entities or creative employment contracts. A public officer, no matter how styled, who works in the public service, no matter how analogous to other constitutional offices, must retire on attaining the age of sixty years, subject to being engaged on a limited period basis as allowed by Article 199(4). If the Constitution is the paramount law, as it should be, then it is emphatically unconstitutional for Parliament to establish an Article 190(1)(d) public service whose officers are not subject to the Article 199 mandatory retirement scheme.

Excellent write up. Very instructive and detailed research. Kudos Prof.