Capacity: A Janus-faced Concept in Ghanaian Jurisprudence

Introduction

“Our word to you does not waver between ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

2 Corinthians 1:18 NLT.

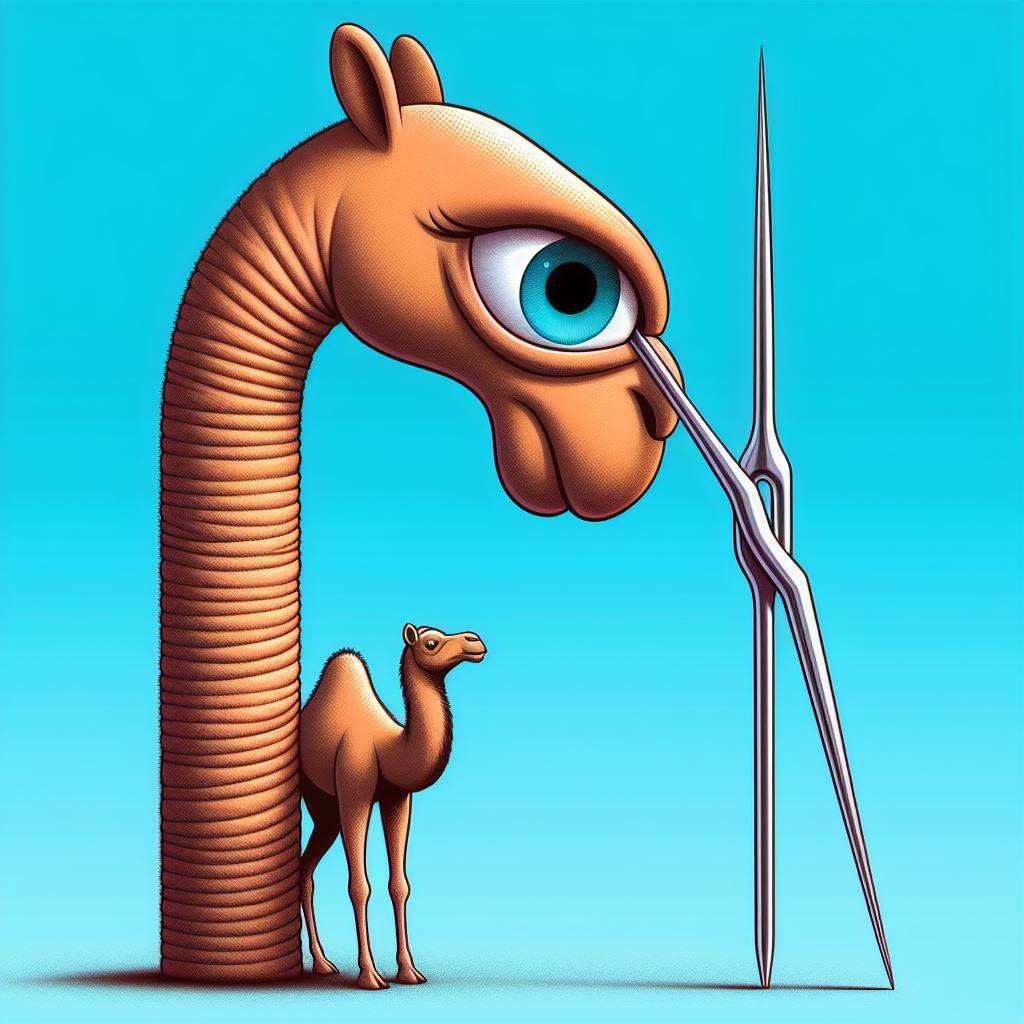

The story of capacity is like the Biblical Reuben. In the Book of Genesis, Jacob said these about his eldest son: “Reuben, thou art my firstborn, my might, and the beginning of my strength … unstable as water, thou shall not excel …”[1].

Indeed, capacity, like jurisdiction, is one of the pioneer and fundamental concepts under our jurisprudence, It is also one of the common law legacies bequeathed to us familiar to all lawyers. It is the very first hurdle to be crossed by a person who wants to patronize the courts; yet, like Reuben, it is very unstable as water. Despite being in existence for a long time, most of its underlying principles as laid down by Ghanaian courts seem to conflict and little effort has been made to synchronise them.

If the Bible warns believers against lukewarm attitude[2] and Paul advised us not to waver between ‘yes’ and ‘no’, then there is every reason for the courts to present to the public a clear unambiguous concept of capacity. Until that is done, the mighty and important concept of capacity will not be of much assistance to the members of the legal fraternity, but will continue to remain as a source of confusion and frustration. I believe it is upon that recognition that the courts in contemporary times have accepted the challenge and are trying to bring some clarity in the law, albeit, at a slow pace. The reality, as observed, is how to identify the source of the problem, being the areas of discrepancies.

The writer considers it imperative to use this paper to unravel some of the underlying contradictory principles on capacity, to aid the courts in their quest to discovering and resolving the inconsistencies in their application.

Capacity and Locus Standi

Capacity as used in the context of civil procedure has been defined as a legal persona (a natural or juristic person) that is capable of vindicating, asserting, or defending a right[3]. Until recently, capacity and locus standi were perceived as one, often used interchangeably by judges. For instance, in the case of Debora Boafo v. Comfort Oduro,[4] Her Ladyship Irene Charity Larbi (Mrs) JA in espousing the principle on capacity said:

“It is trite law among lawyers that the issue of capacity or locus standi is a point of law which can be raised at any time of the trial”.[5]

In 2021, His Lordship Pwamang JSC in Florini Luca & Anor. v. Mr. Samir & Ors.[6] took pains to draw the distinction between the two concepts thus:

“Capacity properly so called relates to the juristic persona and competence to sue in a court of law and it becomes an issue where an individual sues in her own personal right but states a certain capacity on account of which she is proceeding in court. But locus standing relates to the legal interest that a person claims in the subject matter of a suit in court. … generally, locus standi depends on whether the party has a legal or equitable right that she seeks to enforce or protect by suing in court.”[7]

About three months after the decision, the learned Judge further expatiated in George Agyemang Sarpong v. Google Ghana and Google Incorporated LLC supra thus: –

“Although separate, the two (capacity and locus standi) operate as twin concepts for capacity, the power or right to sue, is often bound with a right that exists to be asserted or defended. It is this right that vests a person who has that right or interest with the locus standi … that they are distinct in their significance cannot be denied. In Dallas Fort Worth International Airport v. Cox 261 SW 3d 378 (Court of Appeal of Texas at Dallas) Justice Richter drew the distinction succinctly thus: ‘A plaintiff has standing when he is personally aggrieved, regardless of whether he acts with legal authority; a party has capacity when it has legal authority to act, regardless of whether it has a justifiable interest in the controversy.

If a Court lacks capacity to deal with a Case, can it deal with the merits?

For several decades when the courts found an action to be in want of capacity, two contrasting courses were taken. While some judges ended their judgments on the point of capacity, without endeavouring to delve into the merits or the other issues;[8] others comfortably proceeded to consider the evidence on merits as done by Campbell J. in Lamptey & Anor. v. Neequaye & Ors.[9]

Similarly, in the case of Asante-Appiah v. Amponsa alias Mansah[10], the Supreme Court found that the Plaintiff’s Attorney lacked capacity to initiate the suit and so dismissed it. His Lordship Brobbey JSC stated:

“The failure of the plaintiff to establish the capacity in which the action was prosecuted was sufficient basis on which to dismiss his plaintiff’s claims. Put differently, even before considering the merits of the case, want of capacity alone was sufficient for the plaintiffs to have lost the case (my emphasis).

It was quite surprising, however, that after their Lordships had punctured the capacity of the plaintiff, they advanced to evaluate the entire evidence.

In Yeboah Richard v. Opanin Yaw Manu and Opanin Kofi Boadi of Jankufa,[11] the Court of Appeal took the same course, by discussing the merits of the case after finding that the plaintiff lacked capacity to institute the action.

Not all the judges of the Apex Court agreed that after the failure of a plaintiff’s action on grounds of capacity, the merits of the case should be considered. Therefore, when the opportunity knocked at the door of His Lordship Anin Yeboah JSC (as he then was) in the case of Alfa Musah v. Dr. Francis Asante Appeagyei[12], he formulated the law thus:

“We think the law is that, when a party lacks capacity to prosecute an action the merits of the case should not be considered … If a suitor lacks capacity it should be construed that the proper parties are not before the court for their rights to be determined. A judgment, in law, seeks to establish the rights of parties and declarations of existing liabilities of parties”.

The ratio has received massive support from the courts as gleaned from a plethora of decisions.[13] It is now settled that if an action implodes due to a fundamental defect, such as, want of capacity, limitation or jurisdiction, and the court makes that determination, it is precluded from investigating into the merits of the case, no matter how iron-cast the Plaintiff’s case might be[14]. His Lordship Darko Asare JSC recently provided the guarantee from the highest court of the land that the new conception of the law has come to stay and that they consider themselves as equally bound by it. He disclosed in Manford Gyansa-Lutterodt v. Asam Concept[15] as follows:

“For the law is quite well settled that if any proceedings fail for want of jurisdiction, the trial court and for that matter an appellate court should not proceed to determine the merits of the case, no matter how compelling the facts of the case are … That being the case, we consider ourselves fettered … from probing into the merits of any of the other ground raised in this appeal …”.

Should an action wanting in capacity be struck out or dismissed after evidence had been led?

It is essential that the meaning of the two terminologies (striking out and dismissal) are grasped from the onset. In the Nigerian case of Road Transport Employers Association of Nigeria v. National Union of Road Transport Workers[16], the distinction was clearly drawn thus:

“When a Court holds that a Plaintiff has no locus standi in respect of a claim, the consequential order to be made is striking out of such claim and not a dismissal of the claim. The rationale is that holding that a plaintiff has no locus goes to the jurisdiction of the court before which such an action is brought. When the question that the plaintiff has no locus standi to institute an action arises, all that is being said is that the court before which an action is brought cannot entertain the adjudication of such an action. The Court cannot dismiss a claim, the merits of which it is not competent to inquire into. A dismissal presumes that the court has looked into the claim and found it wanting in merits. But it can only so look into the claim if that claim falls within the Court’s jurisdiction. A dismissal postulates that the action was properly constituted”.

The decision is complemented by the Ghanaian case of Essilfie & Ors. v. Anafo & Ors.[17] in these terms:

“…The concepts of ‘striking out’ and ‘dismissal’ were not the same. When an action or appeal was dismissed it meant that as between the parties it created a bar which would prevent any further proceedings unless permitted by the statute, whereas when an action or appeal was struck out it was always open to the party prejudiced thereby to apply for its restoration”.

It may be realised that the Courts in Ghana have not fashioned out a uniformed procedure when, in their determination of cases, they find that the plaintiff lacks capacity to commence the action. In Andrews Narh–Bi (Substituted by John Nyongmo) & 3 Others v. Asafoatse Kwetey Akorsorku III (Substituted by Asafoatse Kwetey) & Another,[18] the Supreme Court through His Lordship Amadu Tanko JSC in his rendition of the principle where the plaintiff’s capacity has ruptured held:

“It will be a waste of judicial time for the court to engage itself with the merits of a particular matter, only to strike out the action on the basis of want of capacity on the part of the Plaintiff”. (emphasis supplied).

Nevertheless, as far back to the colonial days most judges have been resorting to a dismissal of the action when they find that the plaintiff lacks capacity. In the old case of Chief Sokpui II & Ors. v. Chief Tay Agbozo III & Ors.[19], the plaintiffs sued in a representative capacity in the Native Court for themselves and on behalf of the entire community of Dzelukope. The Court, on discovery that the plaintiffs lacked capacity to commence the action in a representative capacity, dismissed the suit. The Plaintiffs’ appeal to the Land Court was also dismissed.

It must further be reiterated that in the Asante Appiah’s case supra, the Supreme Court in laying down the rule, prescribed a dismissal of the action and not striking out, thus:

“The failure of the plaintiff to establish the capacity in which the action was prosecuted was sufficient basis on which to dismiss his plaintiff’s claims (my emphasis).[20]

The Court of Appeal in several decisions[21] has equally recited the rule with a dismissal of the suit as a consequence where the plaintiff’s action fails on capacity.

Does Striking Out of the Suit really matter?

It has been established that if a suit is disposed of on a legal point, such as capacity, jurisdiction, limitation and res judicata, it should be struck out, but not dismissed. The question is, does it actually matter if the suit is struck out and not dismissed? It may seem that apart from capacity and perhaps, jurisdiction (at times), striking out may have no significant consequence from a case that is dismissed.

If a suit is struck out on grounds of res judicata, it cannot be refiled and may thus, have the same effect as a dismissal. The same consequence pertains to actions struck out for being statute-barred on grounds of limitation. In that respect, though the order would be a mere striking out of the suit, the reality is that the defendant cannot be dragged to court again for the matter to be reopened.

Hence, Lord Greene M.R. could confidently assert in Hilton v. Sutton Stream Laundry[22] thus:

‘Once the axe falls it fails, and a defendant who is fortunate enough to have acquired the benefit of the statute of limitations is entitled, of course, to insist upon his strict right’.

Lord Greene M.R.’s rendition of the law was not only adopted by Apaloo JSC in Akrong v. Bulley[23], but extended to cover capacity thus:

“The question of capacity, like the plea of limitation, is not concerned with merits and as Lord Greene M.R. said in Hilton v. Sutton Stream Laundry (1946) KB 65 at pa. 73, C.A. ‘Once the axe falls it fails, and a defendant who is fortunate enough to have acquired the benefit of the statute of limitations [and I would myself add, or an unanswerable defence of want of capacity to sue] is entitled, of course, to insist upon his strict right’ (my emphasis).

The reformulation of the principle by His Lordship Apaloo JSC under Ghanaian jurisprudence with the addition of capacity[24] seems, with the greatest of respects to the learned judge, to have contributed immensely to the blurring of the distinction between the concepts of striking out and dismissal in our law courts.

While Lord Greene’s illustration above in respect of limitation is by and large unimpeachable, the same cannot be said of Justice Apaloo’s example on capacity. This is because, as I have earlier indicated, a suit thrown out on grounds of limitation cannot be resurrected, but a case thrown out for want of capacity can be refiled and a defendant in the latter scenario would have ‘no right’ to insist on. By way of example, where an attorney’s power to commence an action is found to be defective leading to the striking out of the suit, he can go back to the court if a new valid power of attorney is given. In the same vein, a writ not properly indorsed with the right capacity and thrown out can be re-commenced. A beneficiary who sued without a probate and had his action struck out can return to the court with a fresh action after obtaining probate and vesting assent. Therefore, with capacity, if the axe falls, it does not fall forever to give the defendant special rights to insist upon (unless the action delays and is caught by limitation). Thus, striking out for want of capacity may just be a prelude to the real battle.

What is the effect of the Plaintiff’s want of Capacity on the Defendant’s Counterclaim?

This is another issue hinging on capacity where the Courts’ position tends to conflict. In Nii Kpobi Tettey Tsuru & Ors v. Agri Cattle,[25] the Supreme Court held:

“A counterclaim cannot be maintained when the writ which commenced the action is declared a nullity”.

Then in Huseini v. Moru (2013 -14) 1 SC GLR 363, the Court did not only fortify its previous position, but also justified it at holding 2 thus:

“Since the attorney lacked capacity to issue the writ because the power of attorney was void, the defendant would also not pursue his counterclaim. Even though a counter claim is a separate action from the claim. In the peculiar circumstance of this case, the bottom of the case had been knocked off for want of capacity. If there was no capacity to sue because of the defective power of attorney, then there was no capacity to defend the action.”

In effect, a Counterclaim could be determined by a Court only where the Plaintiff’s capacity is established. However, in 2019, the Supreme Court added a new twist to our jurisprudence, using the conduct of the Defendant (particularly his counterclaim) as the benchmark for determining the success or otherwise of a challenge to the plaintiff’s capacity.

His Lordship Gbadegbe JSC who delivered the Court’s unanimous decision in Subunor Agorvor v. Mr. J.K. Kwao and Aaron Narh Achia[26], pronounced:

“Also, there is the effect of the counterclaim of the defendants against the plaintiff whose capacity they have ceaselessly denied. By the operation of the Rules on pleadings in Order 11 of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, CI 47, the making of the counterclaim against the plaintiff in respect of a disputed land has the effect of constituting an admission that the plaintiff is a competent person to take out the action herein on behalf of his family. Furthermore, Order 81 rule 2 of CI 47, precludes a party who knowingly takes a fresh step in a matter from complaining about a defect in the adversary’s pleading; the technical term employed in the Rules and indeed commonly described by practitioners of the law may be found in Order 81 rule 2 namely ‘fresh step after knowledge of the irregularity’ reading the said rule together with Order 11 on the content of pleadings, it is concluded that the sole ground argued in regard to the want of capacity in the plaintiff is devoid of substance and must fail”.

The understanding one gets from this reasoning of His Lordship is that where a person has admitted the capacity of his opponent, that cannot be questioned again in the proceedings and this admission the Defendant made was by filing a Counterclaim. Having known of the lack of capacity of the Plaintiff and by taking further steps in the proceedings, such as filing a Counterclaim, the Defendants are thereby estopped from questioning the capacity of the Plaintiffs. This position taken by the Apex Court appears not to be in harmony with the accepted legal position that the issue of capacity can be raised at any time of the proceedings.

It needs stressing the point that the Courts had consistently maintained that the issue of capacity goes to the roots of a case[27] and cannot be cured by Order 81 of CI 47.[28] Per the decision in Subunor Agorvor supra, would we be asking too much if we question their Lordships why they did not use the same ‘waiver principle’ under Order 81 of CI 47 to save the Plaintiff’s capacity in its previous decisions in Nii Kpobi Tettey Tsuru & Ors v. Agri Cattle & Huseini v. Moru supra, especially when they did not give any indication that they were departing? In Leslie Nartey Marbell v. Salamatu Marbell[29], while the Court vigorously pursued ‘the implied waiver principle’ in appropriate cases, it was emphatic that the principle cannot prevail when determining the capacity of a Plaintiff.

About two decades prior to His Lordship Gbadegbe’s decision in Subunor Agorvor case supra, Her Ladyship Sophia Akuffo JSC in Kuma v. Morkor[30] had cautioned:

“Where, in fact or law, a person was not a proper party to a suit, then no matter how actively the one had participated in a suit, that person had never being a proper party”.

If His Lordship Gbadegbe’s principle is applied in a situation where a stranger or a person who is not the head of family and does not have the authority of the family commences an action in a representative capacity on behalf of the family and the Defendant succeeds on his Counterclaim, the decision would bind the family even though the person who instituted the action lacked capacity to litigate on its behalf.

It is of little wonder that the Courts have since given the decision by His Lordship Gbadegbe JSC in Subunor Agorvor case a cold shoulder and continue to popularize the Huseini v. Moro position supra. The Court of Appeal’s proclivity to the latter position in Kofi Asamoah v. Nana Guarkro Effah and Kate Adjei[31], George Agyemang Sarpong v. Google Ghana & Google Incorporated LLC[32] & Buokeri Tokuori and Others v. Mwine Kanda[33] is made manifest.

In the very recent case of Andrews Narh–Bi (Substituted by John Nyongmo) & 3 Others v. Asafoatse Kwetey Akorsorku III (Substituted by Asafoatse Kwetey) & Another,[34], the Supreme Court through Amadu Tanko JSC held:

“It is obvious that, the Trial Court committed a fundamental error because a party cannot prosecute a counterclaim against a Plaintiff who is bereft of capacity to have commenced the action in the first place. Having found that the Plaintiff lacked capacity to initiate the action, the Trial Court ought to have struck out the suit as improperly constituted for want of jurisdiction. The converse situation exposes the error of the procedure applied. Per the rules of pleadings, setting up a counterclaim against a party manifests an admission that the said party has capacity to initiate an action and litigate. For purposes of argument therefore, if the trial court’s decision that, the Plaintiff lacked capacity to litigate was right, the court could not, with respect, proceed to deal with and grant the counterclaim of the Defendants against the very non-juristic person who lacked capacity to initiate the action.”

It is suggested, with much diffidence, that the principle propounded by the Supreme Court in Subunor Agorvor v. Mr. J.K. Kwao and Aaron Narh Achia supra should not be nurtured and allowed to sprout.

Can the Plaintiff’s Capacity be attacked for the Suit to be Struck Out pursuant to an Application, but before the filing of a Statement of Defence?

On this, two principles have striven for mastery. The first is the need for a person seeking to challenge the Plaintiff’s capacity to do so in the pleadings.

In Kwabena Acheampong & 2 Ors. v. Seth Welbeck,[35] the Court of Appeal held:

“Traditionally, capacity evokes the court’s jurisdiction to determine the case one way or the other. Thus, the rule or procedure and practice is that such a fact ought to be pleaded so as to allow the party whose capacity is being challenged to be heard on the issue” (emphasis provided).

“It would seem to me that the challenge should be in a statement of defence or cross examination”, opined His Lordship Acquaye J.A. in the case of Kofi Agyemang Paytell Company Limited v. Managing Director Jaah Engineering Company Limited.[36]

The rival principle is to the effect that legal defences, such as jurisdiction, capacity and limitation capable of determining a suit should be raised at the earliest possible stage.[37] This principle is inspired by the fact that capacity may be purely law, facts or both.[38]

Where the capacity being challenged is strictly one of law, such as a plaintiff suing in a representative capacity, but failing to indorse it on the writ and the statement of claim or an attorney who fails to disclose on the writ that he is suing as an attorney for a principal plaintiff, in my humble view, such an application could be raised under the inherent jurisdiction of the court and determined without the filing of a statement of defence.

Her Ladyship Akoto Bamfo (Mrs) JSC in Kwadwo Dankwa & Ors. v. Anglogold Ashanti[39]believes that:

“ … it would be a waste of the Court’s time to insist that a defendant files a statement of defence to plead the same fact. Under the inherent jurisdiction, the court has a duty to terminate claims which are not sustainable”.

Commenting on a similar fundamental legal point, His Lordship Wiredu JSC (as he then was) in the case of In re Sekyeredumasi Stool: Nyame v. Kesse alias Konto[40] advised;

“ .. there is no need to go into the exercise of hearing the whole evidence on the matter again, otherwise its purpose would be defeated. It can legitimately be determined on affidavit evidence in appropriate circumstances”.

In Yortuhor v. Brako & Another[41], Benin J. (as he then was) expressed the possibility of the Court inherently dismissing an action even before the filing of a Statement of Defence. He decided as follows –

“A court has an inherent jurisdiction to dismiss an action which was frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of its legal machinery and process or both. It should be noted that this action could have been dismissed by this court itself even before the defendants had entered a defence because the plaintiff lacked capacity to take the action before it ….” (my emphasis).

Can capacity be determined pursuant to the filing of a conditional appearance?

In the past, it was a normal practice for defendants to file applications to challenge the plaintiff’s capacity pursuant to the filing of a conditional appearance. In Naos Holdings Ltd v. Ghana Commercial Bank,[42] the application to dismiss the suit for want of capacity was filed pursuant to the filing of a Conditional Appearance and before filing a Statement of Defence, but the Supreme Court had no problem with the procedure.[43]

However, in the case of Republic v. High Court Accra. Ex Parte Aryeetey[44], the Apex Court unambiguously held:

“It is not permissible for a defendant who has entered a conditional appearance to move the court to have the writ set aside because he has a legal defence, even if unimpeachable to the action …”

In the same spirit, His Lordship Gyan JA in Ebusuapanyin Kofi Andoh & Ors. v. Ebusuapanyin Asi Yaw[45] decided:

“That a complaint or issue with the capacity of a party cannot under the rules justify an entry of conditional appearance which should lead to an application to dismiss the writ or the action on the score of the Plaintiff’s lack of capacity. Want of capacity may found a defence, but it certainly will not justify an application under Order 9 rule 7 and 8 of the C.I. 47. The process for striking out or otherwise dismissing an action under Order 9 rules (7) and (8) should be distinguished from such a process under Order 11 rule 18 C.I. 47 …. It is obvious that seeking to dismiss the Plaintiff’s action on the ground of lack of capacity on the part of the Plaintiff, following the defendant’s entry of conditional appearance is a fundamentally inappropriate procedural flaw, which makes the said application of the Defendants incompetent”.[46]

Can a person be estopped from raising the issue of capacity?

It is a principle known to every average lawyer that capacity can be raised at any stage of the proceedings, even on appeal. What is not so clear from the principle is whether a person can be estopped from raising the point of capacity? And if capacity is raised and determined in a matter, can it be raised again for the second time after evidence had been led, or even a third time on appeal? The orthodox position of the courts has been to delimit the scope of raising the point of capacity by shutting the door on persons who submitted to judgments.[47]

In the view of His Lordship Kpegah JSC, persons who submit to judgments are forever estopped from denying the capacity of the plaintiff.[48], a position His Lordship Wiredu JSC lends support[49], but His Lordship Abban disaffirms.[50]

In contemporary times, the courts prefer to adopt a liberal approach. Guided by the principle that capacity can be raised at any time, even on appeal, Her Ladyship Prof. (Mrs) Mensa-Bonsu JSC in the case of Kasseke Akoto Dugbartey Sappor & 2 Ors. (Substituted by Atteh Sappor) v. Very Rev. Solomon Dugbatey Sappor (substituted by Ebenezer Tekpetey Akwetey Sappor) & Ors.,[51]surmises that the issue of capacity does not extinguish in a case, stating:

“All the authorities are emphatic that capacity remains a live issue throughout the life of a case…”.

In Union Mortgage Bank Ltd & Ors. v. Alhaji Fatau El-Aziz & 15 Ors. His Lordship Obiri J. defied the issue estoppel rule by asserting that:

“If evidence is led and the Respondent has no capacity to sue, that issue can be raised again. This is because the issue of capacity is not time bound”.

His Lordship Atuguba JSC seemed to have shot down the notion of estoppel on point of capacity in any form in the case of Mary Tetterley Bill & 5 Ors. and Robert Alexander Attuquaye Colley v. Emmanuel Abeka Bill,[52] thus:–

“It is said that when the trial court granted the plaintiffs’ application … no appeal was taken therefrom and that ought to conclude the issue. However, capacity being a fundamental issue, the plea of its foreclosure cannot prevail”.

Conclusion

The authorities are clear that capacity is a fundamental legal concept that goes to the roots of a case and a Plaintiff needs it to be able to invoke the court’s jurisdiction. If it is non-existent, it is a fatality. There is also no dispute about the fact that capacity can be raised at any time in the course of the proceedings, even on appeal. The problem has been that, sometimes, the courts resort to Order 81 with a view to doing substantial justice. Much as a court of law should not close its eyes to the truth when the truth beckons[53] by relying on technicalities to turn away plaintiffs from the driving seat, it is suggested that if a court is minded to save an action in the interest of justice, it must be guided by existing binding authorities and plainly circumscribe the principle it enunciates to the facts and circumstances of that case. The courts, are respectfully urged, to abstain from redefining the concept of capacity in such a way that they would bruise existing binding precedents. That is the only way to save the concept from being perceived as unstable, so that trial judges will no longer have to waver between diverse contrasting positions.

(The issues bordering on capacity under Ghanaian jurisprudence are incalculable and cannot be exhausted in this single paper. I, therefore, assure my readers of continuing with the discussion of the concept in my next edition).

[1] See Genesis 49: 3-4.

[2] Revelations 3:16.

[3] See George Agyemang Sarpong v. Google Ghana and Google Incorporated LLC, Civil App. No. H1/235/2016, dated 28th July 2016, S.C. (unreported).

[4] Debora Boafo suing per her next friend and father Anthony Boafo v. Comfort Oduro and Another, Civil App. No. H1/21/2018, dated 27th February 2019, C.A. (Unreported).

[5] See also Amadu Tanko JA in Aboagye Frimpong v. Madam Mary Mensah, App. No. H1/68/2012, dated 30th November 2012, C.A. (unreported).

[6] Florin Luca & Anor. v. Mr. Samir & Ors., Civil App. No. J4/49/2020, dated 21st April 2021, S.C. (unreported).

[7] See also Ernestina Boateng v. Phyllis Serwah and Others, Civil App. No. J4/08/2020, dated 14th April 2021, SC (unreported).

[8] See cases such as Yorkwa v. Duah [1992-93] 1 GBR 278; Sarkodee I v. Boateng II [1982-83] GLR 715 at p. 724, S.C.& Akrong v. Bulley [1965] GLR 469 at p. 47 at p. 476, S.C.

[9] Lamptey & Anor. v. Neequaye & Ors. [1968] GLR 257, per Campbell J.

[10] Asante-Appiah v. Amponsa alias Mansah [2009] SCGLR 90.

[11] Yeboah Richard v. Opanin Yaw Manu & Opanin Kofi Boadi of Jankufa, Suit No. H1/46/2016, dated 23rd May 2017, C.A. (unreported).

[12] Alfa Musah v. Dr. Francis Asante [2018] DLSC 475.

[13] See Thomas Baiden & Anor. v. Francis Parker, No. J4/58/2022, dated 1st February 2023, S.C, Nana Ngoa Anyimaa Kodom II v. Lydia Anane & Nkua, Civil App. No. H1/04/2011, dated 19th July 2012, C.A., Ebenezer Ogbordjor & 3 Ors. v. AG & IGP [2018] DLCA 6178, HFC Bank (Gh) Ltd v. Jacob Abeka, Civil App. No J4/05/2018, 12th June 2019, SC. & Nana Ababio v. Esther Boahene & Anor., Suit No. OCC/59/12, dated 23rd January 2014.

[14] See the case of Ebusuapanyin Yaw Stephens v. Kwesi Apoh [2010] 27 MLRG 12 at p.26.

[15] Manford Gyansa Lutterodt v. Asam Concepts, Civil App. No. J4/62/2022, dated 20th March 2024, S.C. (unreported).

[16] RTEAN v. NURTW [1992] 2 NWLR 381.

[17] Essilfie v. Anafo [1992] 2 GLR 654 at holding 2.

[18] Andrews Narh-Bi (substituted by John Nyongmo) & 3 Ors. v. Asafoatse Kwetey Akorsorku III (substituted by Asafoatse Kwetey) & Anor., Civil App. No. J4/28/2002, dated 27th July 2023, S.C. (unreported).

[19] Chief Sopkui II v. Chief Tay Agbozo III & Ors. [1951] 13 W.A.CA 241.

[20] See also The Republic v. High Court, Accra, Ex parte Aryeetey [2003-2005] 1 GLR 537 & Lamptey & Anor. v. Neequaye & Ors. supra.

[21] Such as Ama Serwah v. Yaw Adu Gyamfi & Vera Adu Gyamfi [2018] DLCA 4536 & Yeboah Richard v. Opanin Yaw Manu & Opanin Kofi Boadi of Jankufa, Suit No. H1/46/2016, dated 23rd May 2017, C.A. (unreported).

[22] Hilton v. Sutton Stream Laundry [1946] KB 65 at p.73.

[23] Akrong v. Bulley [1965] GLR 469 at p. 476.

[24] See Fosua & Adu Poku v Dufie (Deceased) & Adu Poku Mensah [2009] SCGLR 310.

[25] Nii Kpobi Tettey Tsuru & Ors. v. Agri Cattle, Suit No. J4/15/2019, dated 18th March 2020, S.C. (unreported).

[26] Subunor Agorvor v. Mr J.K. Kwao & Aaron Narh Achia, Civil App. No. J4/07/2018, dated 27th March 2019, S.C. (unreported).

[27] See Fosuah & Adu Poku v. Adu Poku Mensah (2009) SCGLR 310 & Edith v. Keelson (2012) MLRG 127 at p. 137.

[28] Standard Bank Offshore Trust Co. Ltd (substituted by Dominion Corporate Trustees Ltd) v. N.I.B. & 2 Ors. [2017] G.M.J. 113 at p. 174.

[29] Leslie Marbell v. Dalamatu Marbell (2020) GHASC 129 (

[30] Kuma v. Morkor (No. 1) [1999-2000] 1 GLR 721.

[31] Kofi Asamoah v. Nana Guarkro Effah & Kate Adjei, H1/64/2021, dated 24th June 2021, C.A. (unreported).

[32] George Agyemang Sarpong v. Google Ghana Incorporated LLC, Civil App. No. H1/235/2016, dated 28th July 2018, CA (unreported).

[33] Buokeri Tokuori & Ors. v. Mwine Kanda, Civil App. No. H1/18/2009, dated 26th November 2010, CA.

[34] Andrews Narh-Bi (substituted by John Nyongmo) & Ors. v. Asafoatse Kwetey Akosorku III (substituted by Asafoatse Kwetey) & Another, Civil App. No. J4/28/2022, 27th July 2023, SC (unreported).

[35] Kwabena Acheampong & 2 Ors. v. Seth Welbeck, H1/106/2021, dated 16th December 2021, C.A.

[36] Kofi Agyemang Paytell Company Limited v. Managing Director Jaah Engineering Company Limited, Civil App. No. H1/180/2014, dated 21st April 2016, C.A. (unreported).

[37] Infitco Co. Ltd v. Frigo Ltd [2019] DLCA 6204.

[38] Republic v. High Court (Land Division) Accra, Ex parte Lands Commission (Nungua Stool & Ors. – Interested Parties) [2013-2014] 2 SCGLR 1235.

[39] Dankwa & Ors. & Ors. v. Anglogold Ashanti Ltd, Civil App. No. J4/22/2018, dated 14th February 2019, S.C. (unreported).

[40] In re Sekyeredumasi Stool: Nyame v. Kesse alias KoNTO [1998-99] SCGLR 476 at p. 408.

[41] Yortuhor v. Braka & Another [1989-90] 2 GLR 429 at p. 440.

[42] Naos Holdings v. Ghana Commercial Bank [2005-2006] SCGLR 407.

[43] In Polimex v. BBC Builders Co. Ltd [1968] GLR 168, it was held that the proper procedure for a defendant to take in attacking the jurisdiction of the court was by the filing of a conditional appearance.

[44] Republic v. High Court Accra, Ex parte Aryeetey [2003-2004] SCGLR 398.

[45] Ebusuapanyin Kofi Andoh & Ors. v. Ebusuapanyin Asi Yaw [2016] DLCA 141.

[46] See also Marty Nii Danso v. Nii Ayi Okufubour, H1/09/23, dated 20th July 2023, C.A.

[47] See Sarpong v. Yentumi & Anor. [1959] GLR 250 & Gwira v. State Insurance Corporation [1991] 1 GLR 398..

[48] See Republic v. High Court Accra, Ex parte Aryeetey [2003-2004] SCGLR 398 at p.

[49] See Gwira v. State Insurance Corporation [1991] 1 GLR 398

[50] See Waddad Haddad Fisheries v. State Insurance Corporation [1973] 1 GLR 501 at holding 4.

[51] Kasseke Akoto Dugbartey Sappor & 2 Ors. (substituted by Atteh Sappor) v. Very Rev. Solomon Dugbatey Sappor (substituted by Ebenezer Tekpetey Akwetey Sappor) & Ors, Civil App. No. J4/46/2020, 13th January, 2021, SC.

[52] Mary Tetterley Bill & 5 Ors. & Robert Alexander v. Attuquaye Colley v. Emmanuel Abeka Bill, Civil App. No. J4/07/2004, dated 28thJune 2006, S.C. (unreported).

[53] Justice Asiedu JSC in Living Faith World Outreach Centre & Ors. v. The Registrar-General & Ors., No. J4/49/2021, dated 17th May 2023, S.C. (unreported) gave that admonishment.