Today, we turn the clocks back to a key decision that was given 48 years ago. This was in the case of Sallah v Attorney-General. The facts of the case are well known but probably the decision would not have been this popular but for the social and political interests, it generated.

Let’s start from Saturday, 21 February 1970. That day’s edition of the Daily Graphic had just been released. It contained a terse report to the effect that “All persons holding or acting in any office in the public services of Ghana immediately before yesterday shall continue to do so, according to a gazette notice published in Accra.” The report went on to say: “…any person who was notified in writing that his services would not be required after today is not affected by this notice.”

Let’s start from Saturday, 21 February 1970. That day’s edition of the Daily Graphic had just been released. It contained a terse report to the effect that “All persons holding or acting in any office in the public services of Ghana immediately before yesterday shall continue to do so, according to a gazette notice published in Accra.” The report went on to say: “…any person who was notified in writing that his services would not be required after today is not affected by this notice.”

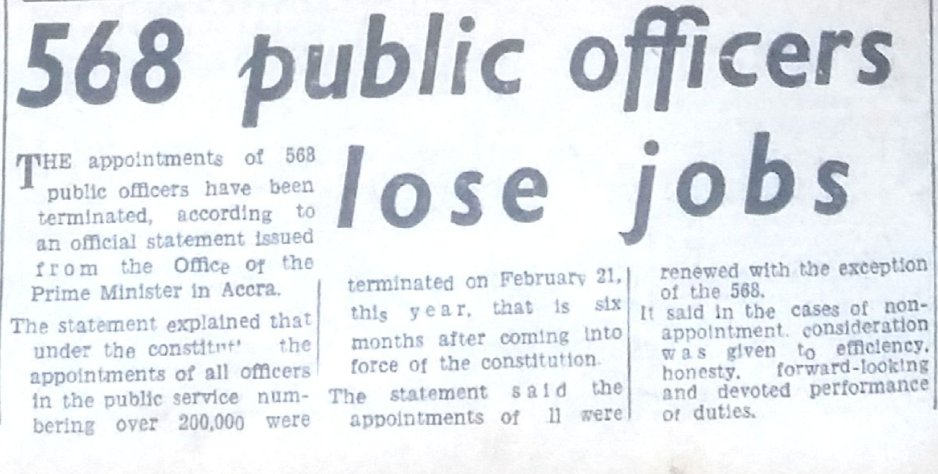

Mr E.K Sallah was one of many who was notified that his services would not be required. He was one of 568 public servants whose appointments in the public service had been terminated. Even though the letters were delivered mostly by hand, the Ghana Air force planes were called in aid for the distribution of letters outside Accra. It had to be done quickly.

Another statement was issued by the office of the Prime Minister. The statement drew the attention of the public to the fact that under the 1969 constitution, “the appointment of all officers in the public service (over 2000 in number) terminated on February 21, 1970 – six months after the coming into force of the of the constitution.” The government cited considerations of efficiency, honesty, forward-looking and devoted performance of duties as some of the reasons that the 568 public officers were not re-appointed[1]. Employees of the Bank of Ghana, the Ministry of Trade, the Ghana Commercial Bank and the Ghana National Trading Corporation were affected (GNTC).

Mr Sallah was a manager of GNTC until he received the letter from the presidential commission signed by Nathan Quao (Secretary to the Presidential Commission). He did not think that there was a legal basis for his termination. He, therefore, contracted the services of Lynes Quarshie-Idun and Company to represent him. He challenged his termination arguing that the law used as justification for his termination did not apply to him. He argued that the GNTC was not established by or in pursuance of the proclamation of the National Liberation Council neither was it established by the authority of the National Liberation Council. He, therefore, sought a declaration that on a true and proper interpretation of section 9(1) of the first schedule of the constitution, the government was not entitled to terminate his appointment.

Days after the writ was issued, Prime Minister Busia granted an interview to the daily graphic. This was on Monday, 2 March 1970. In the interview, he explained: “I have human feelings and am aware that those who have recently been dismissed from the public service have families and some have served for more than 20 or 30 years.” He continued: “Should I allow those who have lost the ability to work hard and efficiently to stop the progress and development of the country while there are young and efficient people who can do the job?” In short, he wanted to save Ghana.

Mr Sallah’s case generated a lot of public interest and discussion. The government’s line of defence was simple –it was the constitution that dismissed Mr Sallah.

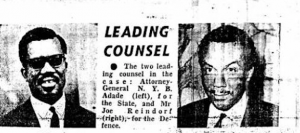

Aside from the huge public interest, the lawyers in the case were giants in their own right. There was Joe Reindorf (who would later on become Attorney-General).Then there was Mr Nicholas Yaw Boafo Adade, the Attorney General (who would later on become a Supreme Court Justice).

Aside from the huge public interest, the lawyers in the case were giants in their own right. There was Joe Reindorf (who would later on become Attorney-General).Then there was Mr Nicholas Yaw Boafo Adade, the Attorney General (who would later on become a Supreme Court Justice).

Nothing was going to be left to chance in this matter. The government needed to win this case. It had dismissed 568 workers and a judicial pronouncement going the other way would have severe consequences for the government (never mind that Mr Sallah was only asking for a declaration). So the Attorney-General threw the spotlight on the judges.

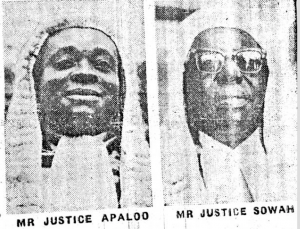

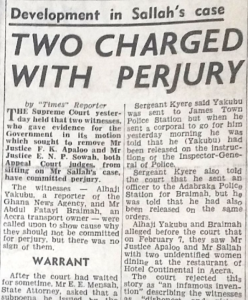

On Wednesday, 25 March 1970, the Daily Graphic reported that the government of Ghana had filed a motion against two judges. There were 5 Judges in the matter. They were Justices Apaloo, Justice Siriboe, Justice Sowah, Justice Ann and Justice Archer. The Attorney-General had concerns about two of these judges. Justice Apaloo and Justice Sowah. The Attorney-General was of the view that the two judges were not going to be impartial arbiters because they had some form of personal interest in the matter.

He, therefore, filed a motion seeking the disqualification of the two. His allegation against Justice Apaloo was that he was Mr Sallah’s close friend. In the case of Justice Sowah, the Attorney-General alleged that he had more than a judicial interest in the matter because his [Justice Sowah’s] brother-in-law’s appointment was also terminated. The Attorney-General alleged that Justice Sowah had gone ahead to discuss the matter with the then minister for external affairs, Mr Victor Owusu.

He, therefore, filed a motion seeking the disqualification of the two. His allegation against Justice Apaloo was that he was Mr Sallah’s close friend. In the case of Justice Sowah, the Attorney-General alleged that he had more than a judicial interest in the matter because his [Justice Sowah’s] brother-in-law’s appointment was also terminated. The Attorney-General alleged that Justice Sowah had gone ahead to discuss the matter with the then minister for external affairs, Mr Victor Owusu.

Once these allegations had been made, they had to be proved. The stage had been set for a fierce trial. The Judges would not simply walk away. They were prepared to see this through. The Attorney General called 3 witnesses. The first two were Alhaji Yakubu (who used to work with the Ghana News Agency) and Abdul Fatal Braimah (a transport owner). They testified that on 7 February 1970, they had gone to see off pilgrims to Mecca and on their return from the airport at about 10 pm, they checked in at the Continental Hotel. It was at the continental hotel that they saw Justice Apaloo in the company of Mr Sallah and two other women. They had also said that the plane took off at 1 am.

Two witnesses were called to rebut the evidence of the two men. One of the witnesses, the duty officer of the Ghana Airways for the night of 7 February 1970, stated in his evidence that the Haj flight to Mecca departed on schedule at 10 p.m. The second witness was a manager of the Hotel Continental restaurant who gave evidence as to the closing time of the restaurant and the nature of the meals served that night at the time when Alhaji Yakubu and his Moslem colleagues Fatayi Braimah allegedly took their dinner.These inconsistencies made Justice Austin Amissah describe the witnesses as untruthful, “dishonest and vicious.” The two men were later charged with perjury.

Airways for the night of 7 February 1970, stated in his evidence that the Haj flight to Mecca departed on schedule at 10 p.m. The second witness was a manager of the Hotel Continental restaurant who gave evidence as to the closing time of the restaurant and the nature of the meals served that night at the time when Alhaji Yakubu and his Moslem colleagues Fatayi Braimah allegedly took their dinner.These inconsistencies made Justice Austin Amissah describe the witnesses as untruthful, “dishonest and vicious.” The two men were later charged with perjury.

Then there was the third witness. Mr Fleischer. He was probably the most believable of all the witnesses. Mr Fleischer worked with Mr Sallah at the Kingsway stores. He told the court that Justice Apaloo and his wife used to visit Mr Sallah at the stores. He also claimed that whenever Justice Apaloo came around, Justice Apaloo spoke to Mr Sallah in a strange language which he did not understand. He said he was sure of one thing though– that in spite of the language barrier, he could tell they communicated in very familiar tones. He also said that Mr Sallah often reserved commodities for Justice Apaloo.

Once again, the court found no merit in Mr Fleischer’s interpretation of events. Justice Amissah made the following conclusions about Mr Fleischer’s testimony: “Turning to Fleischer, it would be a sad day when we have to conclude that in the conditions of this country because a stores manager reserves some commodity for a customer, because that customer looks for and converses with the manager when he comes to the store and in a language which the observer does not understand, because that customer calls that manager by his first name, they must be close intimate friends”.

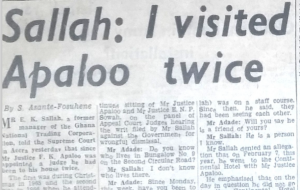

Mr Sallah himself gave evidence. He admitted knowing the party-loving Justice Apaloo and stated that he had been to his house twice for a party since he became a judge.

The majority of the judges were of the opinion that Justice Apaloo and Sowah could go ahead and hear the case involving Mr Sallah.

But there was one person on the bench who did not share that view. Justice Siriboe. He dissented from the majority. For him, he had seen enough to make him believe that his colleagues did not deserve to be on the panel. He said in his dissenting opinion: “The test to be applied to this objection is what a reasonable litigant would think if he gets to hear of matters such as have been alleged in this application, such as the intimate relationship between his opponent and the judge presiding over his case. A reasonable litigant would unhesitatingly form the impression that his case will not be given an unbiased hearing. This would particularly be so in our society where most litigants frown upon a mere conversation between their own counsel and that of their opponents.”

But there was one person on the bench who did not share that view. Justice Siriboe. He dissented from the majority. For him, he had seen enough to make him believe that his colleagues did not deserve to be on the panel. He said in his dissenting opinion: “The test to be applied to this objection is what a reasonable litigant would think if he gets to hear of matters such as have been alleged in this application, such as the intimate relationship between his opponent and the judge presiding over his case. A reasonable litigant would unhesitatingly form the impression that his case will not be given an unbiased hearing. This would particularly be so in our society where most litigants frown upon a mere conversation between their own counsel and that of their opponents.”

With the preliminary objection set aside, the road was clear to hear the substantive claim. Mr Sallah’s lawyer argued that the presidential commission could not terminate Mr Sallah’s appointment because his position fell outside the scope of those offices which the commission could legally terminate. The Attorney-General argued otherwise. Long story short, the court held that Mr Sallah’s appointment was wrongly terminated. The court held that the position held by Mr Sallah did not fall within the purview of Section 9(1) of the transitional provisions of the constitution. The court went on to award costs of NC300 against the government. Justice Apaloo, Justice Sowah and Justice Archer upheld Mr Sallah’s claim. Justice Anin dissented.

With the preliminary objection set aside, the road was clear to hear the substantive claim. Mr Sallah’s lawyer argued that the presidential commission could not terminate Mr Sallah’s appointment because his position fell outside the scope of those offices which the commission could legally terminate. The Attorney-General argued otherwise. Long story short, the court held that Mr Sallah’s appointment was wrongly terminated. The court held that the position held by Mr Sallah did not fall within the purview of Section 9(1) of the transitional provisions of the constitution. The court went on to award costs of NC300 against the government. Justice Apaloo, Justice Sowah and Justice Archer upheld Mr Sallah’s claim. Justice Anin dissented.

But there was one person missing. Justice Siriboe. Justice Siriboe announced his withdrawal from panel hearing the case after he had given his dissenting opinion on the impropriety of his colleagues sitting on the Sallah matter. On the court’s view of Siriboe J.A.’s withdrawal from the panel, the President of the panel gave a statement which is reproduced below:

“STATEMENT BY PRESIDENT AFTER JUDGMENT

We have considered the position which resulted from the fact that our brother Siriboe announced himself as withdrawing from this case. He declined an invitation to sit with us to deliver judgment today. But he took part in this case to its conclusion and also in the judgment conference held on Tuesday March 24 between 9.35 – 12.25 p.m. when a decision was reached. He dissented from the decision of the majority and agreed to articulate his dissent in a judgment to be delivered on April 13.

He says he has withdrawn. We take this to mean that the reason for his dissent is not ready and if it is, it will be made part of the official record.

The Acting Chief Justice informs us that our brother Siriboe has not been excused from this case.

(sgd.) F.K. Apaloo

PRESIDENT.”

While this was ongoing, the Prime Minister and his speech writers were busy preparing a response to the judges.  The speech could not wait. It had to be delivered on that very day. So in the evening of 20 April 1970, there was a television and radio broadcast. Prime Minister Busia had something to say. His response to the judgment was laden in law and could easily have passed for a dissenting opinion. But the tone was aggressive. “I cannot be tempted to dismiss any Judge…I shall neither honour nor deify anyone with martyrdom: But I will say this that the judiciary is not going to hold or exercise any supervisory powers not given to it by the constitution.”

The speech could not wait. It had to be delivered on that very day. So in the evening of 20 April 1970, there was a television and radio broadcast. Prime Minister Busia had something to say. His response to the judgment was laden in law and could easily have passed for a dissenting opinion. But the tone was aggressive. “I cannot be tempted to dismiss any Judge…I shall neither honour nor deify anyone with martyrdom: But I will say this that the judiciary is not going to hold or exercise any supervisory powers not given to it by the constitution.”

Prime Minister Busia talked about how it was important that justice was not only done but seen to be done. He went ahead to cite the respected English Judge Lord Denning on the importance of a judge avoiding conflictual situations. He also cited an English newspaper report of a judge who had recused himself on a matter because of his friendly ties with one of the parties.

Busia went on: “if any others who were not reappointed in the recent implementation of the transitional provisions of the constitution wish to sue the government, they are at liberty to do so. The government will not stop them. But if they hope thereby to coerce the government to employ them, then they will be wasting their time and money. My government will exercise the right to employ only those whom it wishes to employ.”

Then came the (in)famous line: “No court can enforce any decision that seeks to compel the government to employ or re-employ anyone. That will be a futile exercise and I wish to make that perfectly clear.”

In the aftermath of the case, the Attorney-General, Mr Adade, in an interview with the Ghanaian Times stated that the judgment in Sallah’s case was “valueless since the court was constituted by a panel of four instead of five as stipulated in the constitution.” The Acting Chief Justice in response to this issue noted Justice Siriboe had not been excused from the panel. He stressed that the panel was properly constituted.

The clear winner in all of this was Mr Sallah and his lawyer, Mr Reindorf. They had what they wanted. But the relationship between the executive and the judiciary had been deeply bruised; so much so that in the aftermath of the decision, there were calls on the then acting chief justice, Justice Azu-Crabbe to make peace with the executive. His response was simple. “We’ve no tiff with the executive.”

Leave a Reply