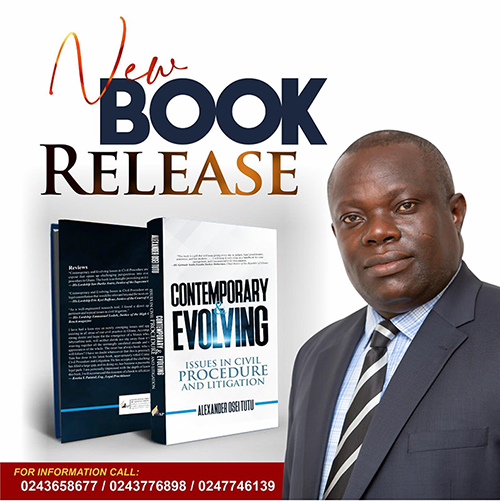

Justice Alexander Osei Tutu’s second publication in recent times, “Contemporary and Evolving Issues in Civil Procedure and Litigation,” is a useful reminder of how the civil procedure rules ought to be and, in fact, should be treated—as an evolving and constant search for efficient means of improving justice delivery in the civil courts. With the search for justice held constant, the author judges the various procedural rules on their merit and ascertains whether they hold any merit. By examining the historical origins and antecedents of some of the procedural rules and practices, the author brings to the fore what in legal circles are considered “trite” and “settled practices” and places them under the spotlight. In a surgical manner, he makes recommendations for improvement and further development of the law.

Using plain, relatable language, the author takes the reader through what in some instances can be a dry and non-exciting area of the law by painting images in the mind of the reader, drawing on familiar experiences, and using this familiar experience as a launch pad to drive home his point.

As the title suggests, the publication does not concern itself exclusively with the civil procedure rules. It delves into other areas of litigation. Regardless of the area ventured into, the common strand is that the author raises and addresses contemporary issues and questions that come up. In 21 chapters, the book considers the courts’ approaches to determining the capacity of litigants to sue or commence an action, and the tricky issue of whether separate plaintiffs in a matter are at liberty to engage separate lawyers. The author also reflects on various decisions of the court on the validity of powers of attorney, wills, the position of the law regarding undisclosed principals in Ghana, and aspects of matrimonial law. The author’s relatable approaches to dealing with various issues in the civil procedure and litigation space sees him posing questions such as, “Is the practice of changing marital names biblical or Islamic?”

Part of the beauty of this publication is the debates and issues it raises. For instance, the author dedicates Chapter 14 of his publication to views expressed by Dr. Justice Srem-Sai in his GhanaWeb publication “Of the Supreme Court, Amidu and Woyome: Qui Tam?” The unwitting aspect of that chapter is that it has given birth to what may be safely described as the “Srem-Sai-Osei Tutu” debate on the question of whether a private citizen who was not acting under the authority of the Attorney-General had the capacity to pursue public monies on behalf of the State.

Like all good books, it is not so much the conclusions that are reached and drawn that are worthy of note. It is the author’s careful exposition of the case law laced with the gratuitous expression of his thoughts that makes it one to look out for. The reader therefore has the benefit of not only the destination but the various stop points in the journey. At the risk of sounding repetitive, the strong point of this publication is not so much the conclusions it reaches but rather the steps leading to the conclusion. In fact, in some instances, the author [perhaps deliberately] falls short of offering any prescriptions but rather chooses to pose and raise questions for further reflections. Commenting on Order 13, Rule 6 of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2004, the author quizzes: “Is the judgment contemplated in this order an interlocutory judgment or a final judgment? If it is interlocutory, why is it not stated clearly in the same manner as Order 13, Rules (2), (3), and (4)? If it was intended to be an interlocutory judgment, would the rule have ended abruptly without specifying the steps to be taken after the judgment as in the other rules?” These kinds of questions, which are raised elsewhere in the book, are not only demonstrative of the open-mindedness of the author but also indicative of the author’s willingness to carry the reader along. The questions contained in the book show signs that the publication is living true to its name. After all, nothing evolves without a barrage of questions.

Coming from a judicial insider, the book may itself be seen as a call for introspection on the relevance of certain legal points and principles or rather the courts’ application of these legal points and principles. The book is littered with instances where technicalities have left hapless persons with legitimate causes of action without remedy based on some technical point. In Chapter 6, the author examines the ever-present tension between balancing justice with procedural technicality. While legal technicalities are vehicles to achieving justice, their application has sometimes left bystanders bewildered and confused at the conclusions they generate.

The outcome of some of these technical points leaves many questioning the essence and utility of the law in the first place. The author premises his decision on the tension between justice and technicalities on Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority v Issoufou [1993-1994] 1 GLR 24, where Aikins JSC explained that “the courts have a duty to ensure that justice is done in all cases…. And should not let this duty be circumvented by mere technicalities.” Staying true to the need not to suppress justice at the expense of technical rules, the learned author in rather understated language noted that: “… there are … a few areas where the courts can do better at suppressing technicalities.” The author concludes this chapter with the following words: “Indeed, the law and its technical rules must bend and give way to substantive justice; otherwise, our calling to dispense justice for the people of Ghana under the 1992 Constitution as judges and lawyers would not be a calling of service but a calling of dabbling in self-aggrandizement with the knowledge we have been blessed with.”

This publication, just as its author, is highly regarded and recommended. And as the Chief Justice of the Republic of Ghana remarked: “This book is a gift that will keep giving every day to judges, legal practitioners, academics, and law students ….”.

Leave a Reply