Introduction

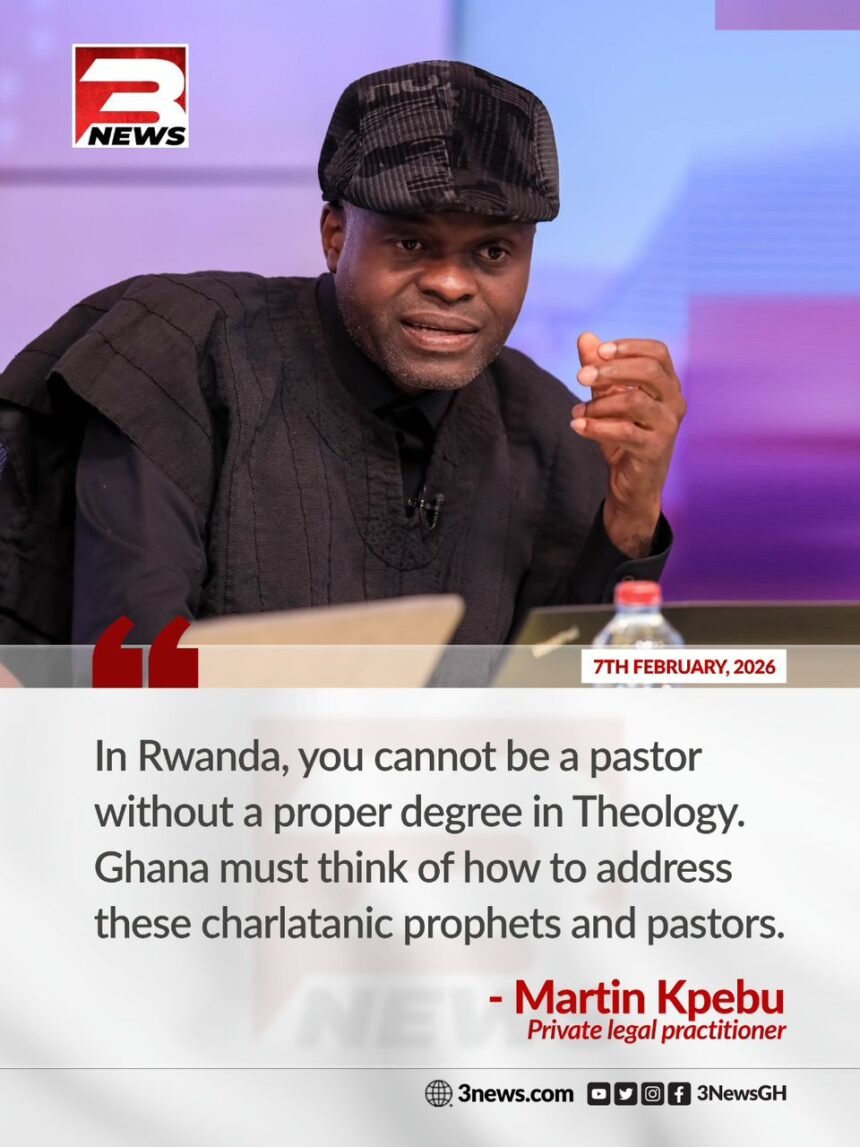

The popular Human Rights Lawyer, Martin Kpebu Esq, has called for the state to regulate religion, drawing an analogy with Rwanda’s requirement that pastors obtain a prior certification in theology to be able to operate as pastors. This background informs the brief analysis in this paper. It aims to analyze why the regulation of religion as practiced in Rwanda would amount to a violation of Article 21(1) (c) of the 1992 Constitution, which guarantees the freedom to practice and manifest religion.

Scope of Rwanda’s Law

In 2018, Rwanda passed the Determining the Organization and Functioning of Faith-Based Organizations, which established a legal framework for regulating religious organizations’ activities.

Article 22 of that law imposed certain limitations/requirements on a person seeking to become a preacher in a religious organization. It required that:

- The person must be of integrity

- Should not have been convicted of the crime of genocide or any crime related to discrimination.

- Must possess a degree in religious studies or any certificate of religious studies from a recognized institution.

Article 2 defines a preacher as: a person authorized by an organization to preach within the organization and who helps followers of the organization in religious matters.

Under Article 7, any association/organization seeking to conduct religious activities must acquire legal personality by registering under Rwandan law.

Ghana’s Constitutional standard for the freedom of Religion

Ghana has a poor (almost non-existent) scholarly & judicial jurisprudence on the scope of freedom of religion. That notwithstanding, a textual examination of Article 21(1)c can provide sufficient core principles which, if jointly explored through a theoretical lens, will reveal enough skeleton to support the muscle of this short piece.

Article 21(1)c anchors freedom of religion with two distinctions: practice & manifestation of practice. This bifurcation is important for understanding, first, the distinctive nature of the practice of religion and its manifestation, and second, to understand the distinct legal framework for both.

The bifurcation, I think, can be explained by employing the philosophies of two prominent political & moral philosophers: John Locke and John Stuart Mill.

In Lockean philosophy, freedom of conscience & belief refers to the holding of religious beliefs without state coercion. [This we can term the non-coercion theory]

J.S Mill’s “On Liberty” sustains a much broader theory. Beyond state coercion, Mill advocated a non-interference theory, except where the manifestation occasions harm to another (the harm principle). [ Non-interference theory]

I believe Ghana’s rights framework combines both Mill & Locke, which I shall demonstrate soon.

Religious practice and manifestation, with their associated legal framework

The term practice of religion appears to mean the traditional art of religious practice, which entails the following acts:

- Holding a belief (holding conscientious scruples)

- Expressing a belief (reading scripture, or expressing a religious doctrine)

- Sharing a belief (proselytizing, evangelizing, preaching)

The term “manifestation of religious practices” encompasses more than the traditional art of religious practice. It includes social, economic, cultural, and spiritual acts that seek to manifest religious doctrines and practices. This may include actions such as erecting a statue, building a church, operating a religious school, and others. All such acts I deem to belong to the sphere of manifestation.

With these two distinctions clearly explained, Lockean and Millian theories are used to flesh out Ghana’s freedom-of-religion framework.

Non-Coercion Framework

In terms of the practice and manifestation of religion, the position of the law is that this right is absolutely guaranteed against coercion. This means that the State cannot compel any individual or group of individuals to hold, practice, or to manifest a religious belief. There is absolute freedom of conscience, and the state cannot reduce any citizen to its religious experimentation process.

Article 56 of the 1992 anchors this point by requiring that:

“Parliament shall have no power to enact a law to establish or authorize the establishment of a body or movement with the right or power to impose on the people of Ghana a common program or a set of objectives of a religiousor political nature.” [ Emphasis]

A distinction must be drawn between religious indoctrination or teaching and moral education. So long as the state is not indoctrinating citizens to adopt a set of religious beliefs, its action in teaching morals such as honesty, truth, courage, virtue, decency, and sociability is permitted. So, in a strictly Lockean sense, non-coercion theory applies in Ghana.

Non-Interference Framework

Regarding interference, the state has limited powers of intervention in the practice and manifestation of religious belief.

The Constitution guarantees the freedom to practice religious belief to a near-absolute extent, except as provided under Article 21(4) (e). Article 21(4)e provides that:

“Nothing in, or done under the authority of, a law shall be held to be inconsistent with, or in contravention of, this article to the extent that the law in question makes provision that is reasonably required for the purpose of safeguarding the people of Ghana against the teaching or propagation of a doctrine which exhibits or encourages disrespect for the nationhood of Ghana, the national symbols and emblems, or incites hatred against other members of the community”

In essence, the expression, teaching, or propagation of religious belief through proselytizing is absolutely permitted, except when a law is enacted to interfere with such expression, teaching, or propagation, which is reasonably limited to the purpose of eliminating doctrines that encourage disrespect for Ghana or its national symbols, or that incite hatred.

Any other law passed by parliament that is not reasonably required for these three purposes cannot be passed to interfere with the practice of religion by absolutely barring it. In that sense, every person is permitted to hold, express, or proselytize a belief, except if it disrespects Ghana or its symbols, or incites hatred among people.

Where the state does not seek to bar the teaching of a belief but only the place, time, or manner of its teaching or expression, Article 21(4)e does not apply. In such place, time and manner cases, Article 12(2) applies.

On the aspect of the manifestation of a religious belief through social, cultural, economic, or other physical actions, the state guarantees freedom to manifest a religious belief except if it is limited under Article 12(2). Article 12(2) provides:

“Every person in Ghana, whatever his race, place of origin, political opinion, color, religion, creed or gender, shall be entitled to the fundamental human rights and freedoms of the individual contained in this Chapter, but subject to respect for the rights and freedoms of others and for the public interest” _ [emphasis]

In essence, where the manifestation of a religious belief will amount to a violation of the rights and freedoms of others or be inimical to public interest, then such manifestation can be limited.

By way of illustration, if a religious belief of a person requires him to smoke cannabis, such manifestation of smoking cannabis can only be limited if it is shown that smoking may violate the rights and freedoms of others or may undermine public interest. This way, a person’s freedom to smoke cannabis for religious purposes may be limited:

- partly if smoking it in public will cause inconvenience to other people or affect other people’s health [ this is why smoking in public can be criminalized]

- Totally, if it can be shown that it may be inimical to the smoker’s health, [ this is why, based on health and welfare concerns, smoking can be criminalized.

Conclusion

I have tried to map out the legal framework of freedom of religion. This theory uses the concepts of non-coercion and non-interference to draw legitimate boundaries for when it is totally or partly unacceptable for the state to coerce or interfere with the practice of religion or the manifestation of a religious practice.

Based on that demonstration, it is clear that the Rwandan law that bans preaching unless one possesses a qualification in theology will constitute an impermissible violation of the religious practice of proselytizing.

Leave a Reply